by Ron Ploof | Jan 6, 2019 | Business Storytelling, Proverbs

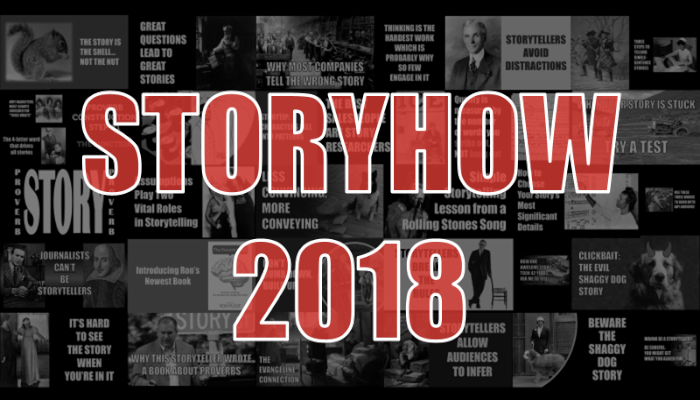

Our goal is to be your one-stop business storytelling resource and we do so by publishing strategies and tactics that help you become a better storyteller. We fulfilled our promise in 2018 through not only publishing the following 32 articles, but Ron also published a new book called The Proverb Effect: Secrets to create tiny phrases that change the world. We look forward to serving your storytelling needs in 2019.

StoryHow Blog Posts (2018)

1. The Evangeline Connection

Variety helps build storytelling stamina. Sometimes its helpful to reach beyond the business storytelling genre to broaden your skills. In this post, Ron practices what he preaches by telling a historical story with personal significance.

2. The Simple Reason Why Most Companies Tell The Wrong Story

Most companies tell the wrong story because they fail to understand the complicated role that their products and services play within an ecosystem of people with different motivations.

3. Use These Three Simple Words to Bond with Any Audience

Looking for an easy way to bond with an audience? Just preface your message with these three little words.

4. Why Marketers Must Always Consider the “Three Whats”

Marketers who want to incorporate storytelling into their messaging must first employ “the three whats.”

5. Three Steps to Telling a Single-sentence Story

Single-sentence stories use carefully chosen words to present facts that defy listener expectations. In this post, Ron describes one of the most emotionally powerful single-sentence stories he’s ever heard.

6. How to Choose Your Story’s Most Significant Details

Sometimes storytelling lessons come from the most unlikely places. This one comes from mathematics.

7. Assumptions Play Two Vital Roles in Storytelling

We all make assumptions. We can’t help it. Which is why they play such important roles in any story.

8. Simple Storytelling Lesson from a Rolling Stones Song

Mick Jagger and Keith Richards offer great advice for any storyteller…through a pop song.

9. How One Awesome Story Took 42 Years for Me to Tell

Sometimes the best stories take a while to tell. This one took me forty-two years.

10. The Four-letter Word that Drives all Stories

The backbone of any story is a simple four-letter word. And it’s not the one you’re thinking of.

11. It’s Hard to See the Story When You’re in it

It’s hard to see the story when you’re in the middle of it. Before we get too confident in our present-day beliefs, remember that we too are in the middle of our own incomplete stories and the only thing standing between us and their endings is time.

12. The Best Salespeople are Story Researchers

The best sales folks aren’t necessarily great storytellers. But they are great story researchers.

13. Quality is measured by the number of words you strike out NOT bang out

It’s not the amount of words you write. It’s about the amount of words you keep.

14. Thinking Is the Hardest Work

Storytellers need time to think, which doesn’t play well in a business culture that demands communications through bulleted presentation slides.

15. Journalists CAN’T be Storytellers

Journalists are beholden to facts. Storytellers are beholden to their audiences. And never the twain shall meet.

16. When Your Story is Stuck, Try a Test

Ron explains one of the techniques that he uses to get unstuck.

17. Great Questions Lead to Great Stories

Have you ever prefaced an answer with “That’s a great question?” In all likelihood, you were about to answer with a story.

18. Beware the Shaggy Dog Story

Have you ever heard a story that seemed so filled with promise yet it never delivered? If so, you’ve been the victim of a Shaggy Dog story.

19. Clickbait: The Evil Shaggy Dog Story

Ron demonstrates how clickbait headline writers use storytelling techniques against us

20. StoryTip: Characters Fall Into Patterns

People enter new situations with previous experiences. Some of those experiences dictate how we act. Great stories come from mismatches in those actions.

21. Don’t Dumb Down. Build Up

The human brain has a tremendous capacity to understand very complex concepts. You just gotta give it a little head start.

22. Story is the shell…not the nut

Some things in life give their lives for others. Stories are no exception.

23. Storytellers Allow Audiences to Infer

Bad storytellers describe meaning explicitly. Great storytellers allow their audiences to infer it themselves.

24. Wanna be a storyteller? Be careful what you ask for

Storytelling is a superpower. But it also comes with its own Kryptonite.

25. Storytellers Break the Rules

Advertising legend Stan Freberg shows us how the best storytellers break the rules.

26. Introducing The Proverb Effect

Ron introduces The Proverb Effect, the first book to define a repeatable process for conveying deep meaning through self-created proverbs.

27. Why this Storyteller Wrote a Book about Proverbs

Storyteller Ron Ploof wanted to know how proverbs have been used successfully to pass wisdom from one generation to another. Two years of research later and he’s figured out the rules for creating the ultimate long-story short.

28. Less Convincing, More Conveying

Deception experts say that liars convince, while truth-tellers convey. Which of the two terms best describes your marketing materials?

29. Storytellers Avoid Distractions

The worst thing that a storyteller can do is introduce a distraction to the audience.

30. Bookend Your Next Talk with Proverbs

Ron Ploof introduces the StoryHow™ PSP method of structuring your next talk.

31. Creating Proverbs: The Function

Proverb construction is a three step process. This post is about Step 1: determining a function.

32. Proverb Construction Step #2: The Frame

Proverb construction is a three step process. This post is about Step 2: determining a proverb’s frame.

by Ron Ploof | Nov 12, 2018 | Business Storytelling

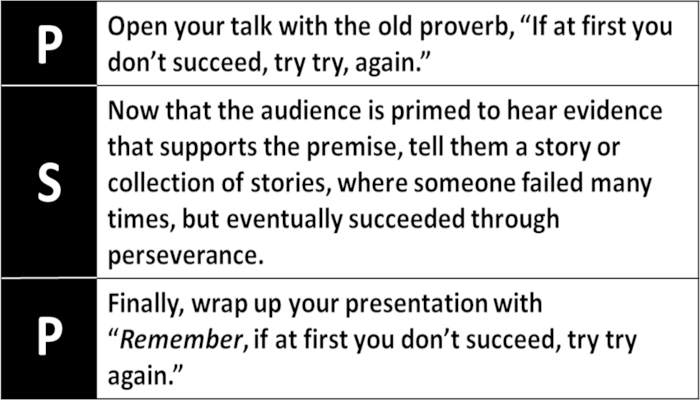

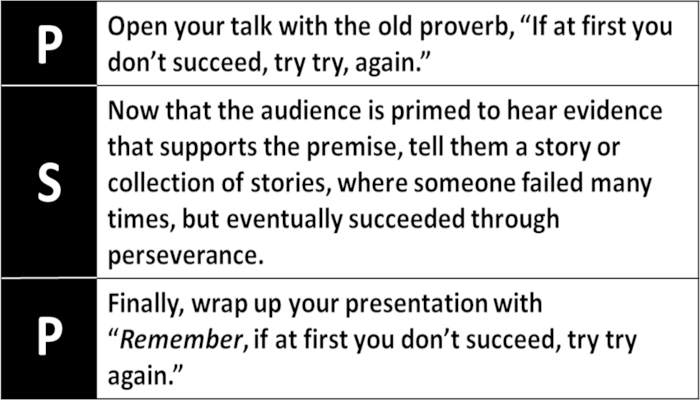

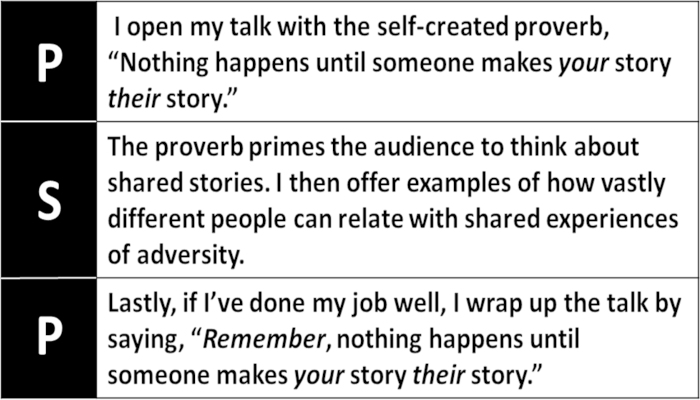

So, you have a big idea, need to share it with an audience, and are looking to structure your talk. How do you choose a beginning, middle, and end? Have you considered using the StoryHow™ PSP method?

In my recent book, The Proverb Effect, I teach how old proverbs have helped teachers teach and students learn for thousands of years. Something in their linguistic structure gives proverbs the unique capability to act as both premise and conclusion. PSP uses this dual capability to open your talk using proverb as a premise, follow it with story-based examples, then wrap it all up by repeating the proverb as a conclusion. PSP helps you open and close strong.

For example, let’s use PSP to structure a talk about the power of persistence.

The method is effective because the human brain is comfortable listening to stories and proverbs are the ultimate long-stories short.

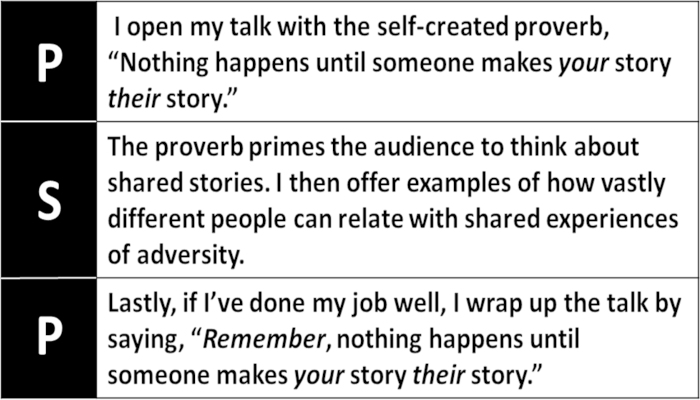

The first example used an old proverb, but perhaps you want to use one of your own. Here’s an example of one of my PSP talks.

Let’s say that I want to share the big idea that people will only join your cause if they can relate personally with it.

Give it a try. Use PSP to structure your next talk using the following steps:

- Convert that big idea into a proverb

- Open your presentation with it

- Offer evidence through stories

- Cap off your talk by putting the word remember before your proverb

Give PSP a try and let me know how it worked out.

by Ron Ploof | Oct 29, 2018 | Business Storytelling

One of my movie-watching pet peeves is non-musician actors playing instruments. My issue usually manifests itself as a mismatch between the video and soundtrack. For example, as a percussionist, I’m highly sensitive to non-musician drummers waving their arms without hitting anything, or even worse, striking cymbals, snare drums or tom-toms out of sync with the soundtrack. And don’t even get me started about non-musician guitar players. There is nothing more frustrating than watching an actor strumming clumsily while sliding his lifeless hand along the guitar’s neck without any attempt at playing a chord. Such distractions negatively impact my willingness to suspend belief.

All storytellers must fix story problems. In the case of the non-musician actor, visual storytellers must find a movie-magic way to cover up the fact that the actor can’t play. One technique is to hide the musician’s hands, either by using an obstructed camera angle (behind the piano), or a tight shot on the hands of a “stunt musician.” Both techniques, however, tend to draw my attention to the problem as I want to see a full-frame shot of the character playing.

I’ve always wondered, why can’t they just teach the actor how to play something—ANYTHING—to augment the various cuts with at least one full-frame shot? Anyone can learn to play a few guitar chords or play a simple drum beat for a few seconds.

Non-musician actors aren’t the only distractions that pull me out of a story. Consider these other distracting storyteller fixes:

1. The antagonist needs a mysterious device that can be used to destroy the world. What’s the easiest way to go? Use a “microchip.”

2. A crime fighter reviews video footage of a getaway car. The storyteller chooses between two uninspired ways to extract information from the video: a) zoom in to read a perfectly clear version of the license plate (which is impossible from a picture-resolution perspective) or b) have the character acknowledge the zooming-in problem, but can “clean it up” through magical image processing software…or a microchip!

3. And my all-time favorite…the cops are stumped for clues, so, they approach some clairvoyant petty thief. “Word on the street,” the informant says, “is that Mr. Big is gonna hit the bank tonight at midnight.” Really? Mr. Big shares such information with the guy selling stolen watches on the corner?

Storytellers have an obligation to hold their readers attention, thus must solve their problems in a believable way. Ask yourself, does my story have too much detail, too few characters, or too many plot twists? Are the solutions to my story problems realistic or do they cause distractions? Tackling these issues now will save much grief in the future.

Photo Credit: Mayer, Frank Blackwell. The Continentals / FBM. , 1875. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2006680120/.