We were taught as children to always tell the truth because truth-telling is good and lying is bad. Then, as we grew up, we learned that this truth thing wasn’t so black and white. Evidently, sometimes deception is not only acceptable, but it’s also appreciated.

For example:

- When a nurse distracts a child who’s terrified about an impending injection

- When a comedian sets up a punchline

- When a magician uses sleight of hand to create an illusion

And so we adapted, telling truths and non-truths, depending upon situations. I’ve learned that the best way to distinguish between the two is to consider the Benefit Rule1 by asking:

Who benefits from the lie, the deceiver or the deceived?

Think about a man who encourages his girlfriend to spend the evening with her friends so that he can cheat on her. Now consider a man orchestrating the same ruse to occupy her time while he prepares a marriage proposal. The same deception scenario produces different ethical results based on the deceiver’s motivations. If the beneficiary of the deception is the deceiver, it’s unethical. If the deceived received the benefits, it’s ethical.

The best storytellers deceive. Without the ability to do so, stories become predictable and boring. And so, storytellers toil to balance both the information and the timing of that information to keep things interesting. George Lucas, for example, did so by hiding the fact that Luke and Leia were siblings and that Darth Vader was their father.

So, how can we become masters at ethical deception? The answer comes from an unexpected place–our judicial system.

Witnesses in an American courtroom take an oath “…to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth.” This seemingly innocuous phrase contains a beautifully complex concept that describes three distinct classes of deception.

“All the lies that have ever been told or ever will be told fall into three categories, or strategies: lies of commission, lies of omission, and lies of influence.” 2

- A lie of commission is a bald-faced, flat-out untruth

- A lie of omission is subtler. Rather than telling the whole truth, the deceiver selectively reveals verifiable facts, yet omits the less convenient ones. For example, consider the teenager who broke curfew. When asked, “Where were you?” she answers with a verifiable “I was at the library,” which is true. She just omitted the part about the house party she attended afterwards.

- A lie of influence (which I prefer to call a lie of conflation) is the most complex of the three. It involves adding extra facts to obfuscate the truth. For example, when asked, “Did you steal the cookie?” the confectionery bandit explains, “You know that I don’t like sweets. Remember that time in the bakery?”

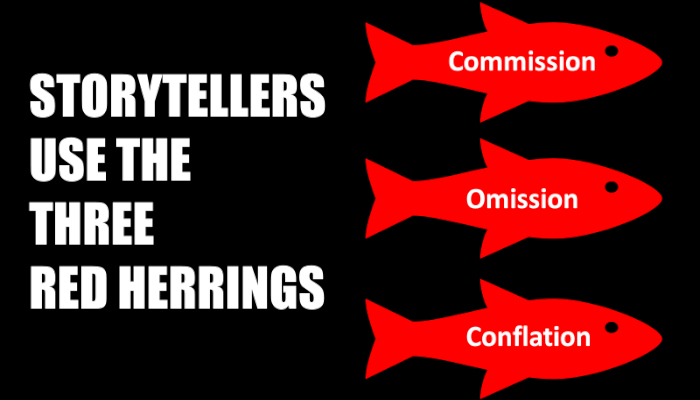

The best storytellers deceive ethically. They use the three red herrings: commission, omission, and conflation to keep an audience on its toes. If done right and the audience benefits from the deception, they’ll thank you for it.

Now it’s your turn. The next time you tell a story, how will you use the three red herrings?

Notes:

- Ron Ploof, The Proverb Effect (Aliso Viejo, CA: OC New Media, LLC, 2018) p. 22.

- Susan M. Carnicero and Philip Houston, Spy the Lie: Former CIA Officers Teach You How to Detect Deception (Columbus, OH: Ohio State Bar Association CLE, 2012), Kindle Location#: 606.

Oh, and if you were looking for the answer to the last week’s cliff hanger…I don’t own a patent. 😊