by Ron Ploof | Jan 13, 2019 | Proverbs

This is the last post in our series of proverb construction, so if you’re reading this first, we suggest that you go back and review:

Proverb Construction Step #1: The Function

Proverb Construction Step #2: The Frame

All written works consist of form and function. Proverbial form is split into two subcategories: frames (the structure by which we build our proverbs) and finishes (the techniques used to gussy ’em up). We’ll wrap-up our series with finishes.

Finishing is my favorite part of proverb construction because it gives me the creative freedom to add style to the drabness of function and form.

Proverb finishes come in five categories: conviction, ellipsis, negation, poetic, and wordplay:

- Conviction sets the confidence level of the proverb through using words such as always, sometimes, or never as in: sometimes blessings come in disguise

- Ellipsis truncates proverbs to just the essential words—sometimes eliminating the verb entirely, such as in: least said, soonest mended

- Negation uses negative logic to make points through words like no or not as in one swallow does not a summer make

- Poetic finishes add to the memorability and repeatability of proverbs. There are five different poetic types to consider: rhyme, rhythm, assonance, alliteration, and consonance.

- Rhyme uses a collection of same-sounding word fragments such as meet roughness with toughness

- Rhythm arranges syllables to form a beat, such as in nothing ventured, nothing gained, which follows the beat pattern of one-two; one-two; one-two-three

- Assonance is like rhyme, where it uses repeating vowel sounds. While time and nine don’t rhyme in a stitch in time saves nine, the two words are tied together through the common pronunciation of the long “I” sound

- Alliteration repeats a consonant sound at the beginning of a word, as in it takes two to tango

- Consonance is like alliteration, yet the consonance sounds are found in the middle and end of words as opposed to the front of them, such as: one day a rooster, the next day a feather duster

- Wordplay involves a clever use of words. There are four wordplay subcategories: associations, double-use, opposites, and reversals.

- Associations play with the relationships between word meanings. For example, a clever hawk hides its claws uses the association between a bird of prey and its talons

- Double-use finishes repeat words to make a point, such as in a friend to all is a friend to none

- Opposites make their points paradoxically, through contradictory or metaphorical meanings, such as one man’s gravy is another man’s poison

- Reversals are like double-use finishes because they repeat words but differ by reversing their order. For example, it’s not the size of the dog in a fight, but the size of the fight in the dog

RECAP

So, there you have it: the three steps for proverb construction:

- What’s the function of your proverb? (definition, prediction, or prescription)

- What frame will you build the proverb upon? (comparisons, conditionals, derivatives, none)

- What finishes can you add? (conviction, ellipsis, negation, poetic, or wordplay)

Give it a try.

by Ron Ploof | Jan 6, 2019 | Business Storytelling, Proverbs

Our goal is to be your one-stop business storytelling resource and we do so by publishing strategies and tactics that help you become a better storyteller. We fulfilled our promise in 2018 through not only publishing the following 32 articles, but Ron also published a new book called The Proverb Effect: Secrets to create tiny phrases that change the world. We look forward to serving your storytelling needs in 2019.

StoryHow Blog Posts (2018)

1. The Evangeline Connection

Variety helps build storytelling stamina. Sometimes its helpful to reach beyond the business storytelling genre to broaden your skills. In this post, Ron practices what he preaches by telling a historical story with personal significance.

2. The Simple Reason Why Most Companies Tell The Wrong Story

Most companies tell the wrong story because they fail to understand the complicated role that their products and services play within an ecosystem of people with different motivations.

3. Use These Three Simple Words to Bond with Any Audience

Looking for an easy way to bond with an audience? Just preface your message with these three little words.

4. Why Marketers Must Always Consider the “Three Whats”

Marketers who want to incorporate storytelling into their messaging must first employ “the three whats.”

5. Three Steps to Telling a Single-sentence Story

Single-sentence stories use carefully chosen words to present facts that defy listener expectations. In this post, Ron describes one of the most emotionally powerful single-sentence stories he’s ever heard.

6. How to Choose Your Story’s Most Significant Details

Sometimes storytelling lessons come from the most unlikely places. This one comes from mathematics.

7. Assumptions Play Two Vital Roles in Storytelling

We all make assumptions. We can’t help it. Which is why they play such important roles in any story.

8. Simple Storytelling Lesson from a Rolling Stones Song

Mick Jagger and Keith Richards offer great advice for any storyteller…through a pop song.

9. How One Awesome Story Took 42 Years for Me to Tell

Sometimes the best stories take a while to tell. This one took me forty-two years.

10. The Four-letter Word that Drives all Stories

The backbone of any story is a simple four-letter word. And it’s not the one you’re thinking of.

11. It’s Hard to See the Story When You’re in it

It’s hard to see the story when you’re in the middle of it. Before we get too confident in our present-day beliefs, remember that we too are in the middle of our own incomplete stories and the only thing standing between us and their endings is time.

12. The Best Salespeople are Story Researchers

The best sales folks aren’t necessarily great storytellers. But they are great story researchers.

13. Quality is measured by the number of words you strike out NOT bang out

It’s not the amount of words you write. It’s about the amount of words you keep.

14. Thinking Is the Hardest Work

Storytellers need time to think, which doesn’t play well in a business culture that demands communications through bulleted presentation slides.

15. Journalists CAN’T be Storytellers

Journalists are beholden to facts. Storytellers are beholden to their audiences. And never the twain shall meet.

16. When Your Story is Stuck, Try a Test

Ron explains one of the techniques that he uses to get unstuck.

17. Great Questions Lead to Great Stories

Have you ever prefaced an answer with “That’s a great question?” In all likelihood, you were about to answer with a story.

18. Beware the Shaggy Dog Story

Have you ever heard a story that seemed so filled with promise yet it never delivered? If so, you’ve been the victim of a Shaggy Dog story.

19. Clickbait: The Evil Shaggy Dog Story

Ron demonstrates how clickbait headline writers use storytelling techniques against us

20. StoryTip: Characters Fall Into Patterns

People enter new situations with previous experiences. Some of those experiences dictate how we act. Great stories come from mismatches in those actions.

21. Don’t Dumb Down. Build Up

The human brain has a tremendous capacity to understand very complex concepts. You just gotta give it a little head start.

22. Story is the shell…not the nut

Some things in life give their lives for others. Stories are no exception.

23. Storytellers Allow Audiences to Infer

Bad storytellers describe meaning explicitly. Great storytellers allow their audiences to infer it themselves.

24. Wanna be a storyteller? Be careful what you ask for

Storytelling is a superpower. But it also comes with its own Kryptonite.

25. Storytellers Break the Rules

Advertising legend Stan Freberg shows us how the best storytellers break the rules.

26. Introducing The Proverb Effect

Ron introduces The Proverb Effect, the first book to define a repeatable process for conveying deep meaning through self-created proverbs.

27. Why this Storyteller Wrote a Book about Proverbs

Storyteller Ron Ploof wanted to know how proverbs have been used successfully to pass wisdom from one generation to another. Two years of research later and he’s figured out the rules for creating the ultimate long-story short.

28. Less Convincing, More Conveying

Deception experts say that liars convince, while truth-tellers convey. Which of the two terms best describes your marketing materials?

29. Storytellers Avoid Distractions

The worst thing that a storyteller can do is introduce a distraction to the audience.

30. Bookend Your Next Talk with Proverbs

Ron Ploof introduces the StoryHow™ PSP method of structuring your next talk.

31. Creating Proverbs: The Function

Proverb construction is a three step process. This post is about Step 1: determining a function.

32. Proverb Construction Step #2: The Frame

Proverb construction is a three step process. This post is about Step 2: determining a proverb’s frame.

by Ron Ploof | Dec 17, 2018 | Proverbs

All written works consist of form and function. Since form is more complicated than function (see last post), we’ll need to spread our discussion about it across a few posts.

Proverbial form is split into two major pieces: frames (the structure by which we build our proverbs) and finishes (the techniques used to gussy ’em up). Today we cover frames.

Frames come in four categories: Metaphor/Definition, Comparison, Conditional, and Special

1. Metaphor/Definition

Metaphor is the building block of all proverbs, thus it deserves its own frame category. Proverbs built upon metaphor/definition frames include:

- time is money

- ignorance is bliss

- a diamond is forever

2. Comparisons

Comparison frames juxtapose certain roles, events, and influences to make a point. They frequently contain qualifying terms such as better, best and worse:

- It’s better to have loved and lost than have to have never loved at all

- Old friends and old wine are best

- False friends are worse than open enemies

3. Conditionals

Conditional frames establish situational advice. They typically contain setup words like if and when:

- If the shoe fits, wear it

- If you lose your temper, don’t look for it

- When EF Hutton speaks, people listen

4. Special Frames

And lastly, a subset of frames exists that may contain metaphor/definition, comparison, or conditional elements, but do so uniquely. There are two special frame subcategories: derivatives and implied.

4a. Derivative (Special)

Derivative proverbs are built upon well-established sayings and cultural references, thus they come spring-loaded with memorability. Many carry humor which lowers the barrier to listener adoption and increases the likelihood that the proverb will be repeated. My favorite derivative proverb results from the combination of two other proverbs:

A rolling stone gathers no moss + open mouth insert foot = a closed mouth gathers no foot

My storytelling buddy Park Howell used an iconic song as a derivative frame to form:

a spoonful of story helps the data go down

(Can’t ya just hear Julie Andrews singing it?)

4b. Implied (Special)

Finally, while all proverbs are based in metaphor and formed upon frames, sometimes those frames get eliminated during the editing process. For example, let’s take the proverb no pain no gain. Note the absence of telltales for comparisons (better/best/worse) nor conditionals (if/then/when). Does this mean that the proverb has no frame?

We’ll dive deeper into this topic when we talk about finishes, but proverb creators start with a big idea, determine a function and a frame, and then iterate through an editing cycle to make the proverb more memorable and repeatable. Sometimes this process eliminates telltales (better/best/worse/if/then/when) while simultaneously leaving behind cognitive references to them.

For example, perhaps the first incarnation of no pain, no gain read: If you want to gain, you must experience pain before some sharp copy editor chopped those nine words to four. And although the proverb lost its conditional telltale (if), cognitive frame references remain in the minds of both speaker and listener. The speaker implies the conditional frame while the listener infers it.

Now it’s your turn. Examine your favorite proverbs. Can you determine their functions and frames? The better you are at deconstructing existing proverbs, the better you’ll be with creating your own.

If you want to learn more about proverbs, grab a copy of The Proverb Effect on Amazon.com.

Photo Credit: Extension of library of Harvard College, Iron details. Ware and Van Brunt architects / Wm. C. Richardson, del. Cambridge Massachusetts, 1878. Boston: Heliotype Printing Co. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2007682661/

by Ron Ploof | Dec 2, 2018 | Proverbs

Last post, I described the StoryHow™ PSP method of building a talk. The technique has speakers open with a proverb, offer evidence via a story, and finally close with that proverb. While the same proverb is used to bookend the story, its purpose is different. The first instance acts as a premise and the second as a conclusion. In this post, I describe the first of a three part process for creating your own proverbs.

Whether you’re sharing an opinion, giving advice, or just leaving your audience with something to chew on, you first must make a choice. What are you trying to accomplish? What do you need your message to do? In the language of proverbs, you need to determine your function.

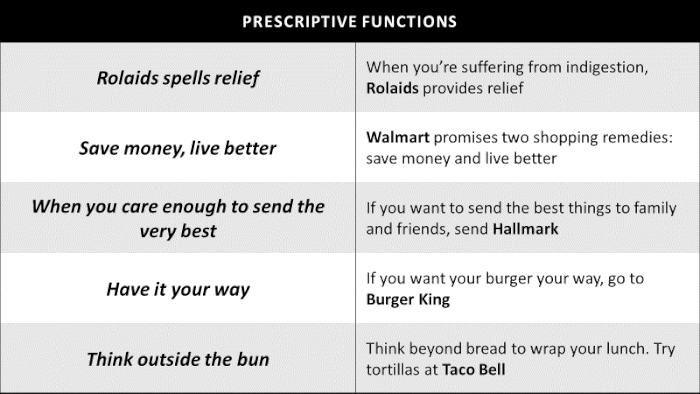

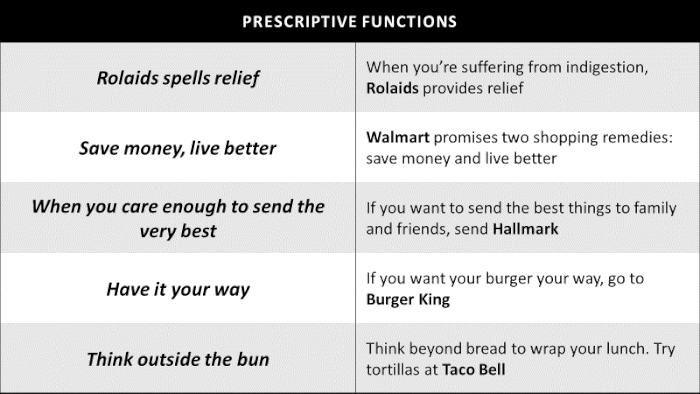

Proverb functions come in three forms: definitions, predictions, or prescriptions:

- Definitions describe one thing in terms of another. They typically contain words like is, are and like

- Predictions illustrate a cause and effect relationship to show how one event leads to another

- Prescriptions offer ways to either solve or prevent a problem

I’ve found that the best business taglines are proverbish, so let’s use a few to learn about the differences.

So, now it’s your turn. What’s your favorite business slogan? Can you determine it uses definition, prediction, or prescription?

If you want to learn more about proverbs, grab a copy of The Proverb Effect on Amazon.com.

Sources:

-

- https://superdream.com/news-blog/best-advertising-slogans

- http://examples.yourdictionary.com/catchy-slogan-examples.html

Photo Credit: Clarence H. White School Of Photography, Steiner, Ralph, photographer. Typewriter Keys. , 1921. , Printed 1945. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2004666344/

by Ron Ploof | Oct 8, 2018 | Proverbs

According to a 2016 study by Pew Research, 20% of Americans feel overwhelmed by the deluge of information that they face every day. A 2015 Microsoft® study revealed a side effect to this information overload—that the average human attention span has dropped from 12 to 8 seconds, making it shorter than that of a goldfish. And the problem is getting worse as our social networks ping us incessantly, Russian bots spread fake news, and machine learning gobbles up this content to create even more.

The problem? We are meaning-seeking beings paddling rudderless in a sea of non-contextualized information. We yearn to understand and to be understood. And yet, without an effective way to do so, we make snap judgments, adopt extreme political views, and ultimately pull our communities apart when we should be pulling them together. If we’re to extricate ourselves from this funk, we need less information and more meaning.

But how can we convey our thoughts succinctly? How can we fill this meaning-gap without contributing to the information overload problem? I began finding answers in a short, narrative story-form that humans have used since the invention of language: the proverb.

Proverbs are tiny linguistic devices that convey more meaning than the words used to construct them. They’re policies for making better life decisions, passed from the experienced to the inexperienced. The simplicity of their presentation lies in stark contrast to the complexity of their function. Proverbs are both objective and subjective and contain both premise and conclusion. They are accepted generally yet applied specifically. And since their power of persuasion comes from both logic and emotion, they wrap their inductive and deductive reasoning in literary devices such as symbolism, alliteration, rhyme, and rhythm.

I’ve learned much about these little powerhouses during my two years of collecting and studying them. For example, after running fifteen-hundred English proverbs through linguistic analyses, I found that proverbs are not only short (all 1,500 contain less than 129 characters), but they are also easy to read (4.75 grade reading level). In other words, proverbs are both tweetable and…wait for it…you don’t need to be smarter than a fifth-grader to understand them. Their dual ability to help proverb-speaker’s teach and proverb-listener’s learn is a testament to their immense power. And most importantly, proverbs are universally-human, as they’re found throughout history, across all languages, nationalities, cultures, and creeds. The Proverb Effect is the first book to define a simple and repeatable process to convey one’s deep meaning through self-created proverbs.

Wisdom is gained through experience and shared through proverbs.

by Ron Ploof | Sep 27, 2018 | Proverbs

Three years ago, I published a deck of playing cards that helps people apply storytelling to their business communications. The StoryHow™ PitchDeck is now being used by business storytellers in 24 countries. Today, I’m announcing a new addition to the StoryHow™ family of products–a book that teaches a deceptively-simple technique that great communicators have used since the invention of language. Some call them idioms or wise old sayings, but we’ll call them proverbs, like:

- Slow and steady wins the race (Aesop, ~550 BC)

- Don’t put off until tomorrow what you can do today (Chaucer, late 1300s)

- Stupid is as stupid does (Gump, 1994)

Proverbs are the ultimate long-stories short. They’re universally human, and thus effective across time, culture, and language. And while it’s tempting to dismiss them as droll or trite, doing so just underestimates the powerful roles they play in both human understanding and teaching. The Proverb Effect is the first book to define a repeatable process for conveying deep meaning through self-created proverbs.

I wrote The Proverb Effect to help you become a better writer, speaker, and teacher. Read it to learn:

- Why proverbs reign supreme over other message types

- What makes proverbs the triple-threat of communications: memorable, repeatable and most importantly, persuasive.

- A step-by-step methodology to apply the most powerful communications device in human history

Lastly, in addition to teaching people how to tell stories, I’m also a working storyteller. So, I wrote The Proverb Effect as a business fable. It’s the story of Samantha Kim, a young project manager whose disastrous presentation sets her on a journey to become a better communicator. She meets Tina, who teaches her how to convey deep meaning through studying everyday proverbs. When Sam’s company loses its largest client, the resulting financial crisis threatens her firm’s very existence. Can Sam learn enough from Tina to win back the client, save her company, and finally redeem herself from the disastrous presentation? The Proverb Effect has the answers.

I’m very excited about sharing this new project with you. Stay tuned for more information as we get closer to the release date.