by Ron Ploof | May 2, 2016 | Business Storytelling

“What makes a story different from other forms of writing?” the young marketer asked me after one of my talks.

“Change,” I said, before telling the following story.

My family stores our dry goods on a shelf in the garage. One day last summer, while my wife was putting something onto that shelf, she ran into something that had interrupted her normal routine…

…a three-foot rattlesnake.

There’s nothing like coming face-to-face with a deadly being. The experience elicits a primal response that’s involuntary and automatic. Adrenaline courses through your veins, your heart rate elevates and your attention becomes laser-like. It’s a suspended moment in time, where nothing else matters until the threat is removed.

A rattlesnake is a perfect metaphor for the beginning of any story because it signals a break from routine. Without the snake, my wife would have placed the item on the shelf without notice as she had hundreds of times before. But with the snake, she needed to adjust her priorities quickly.

Change is the catalyst of the human condition. When it’s absent, we feel safe. But when a familiar pattern is broken, like the lights go out, quarterly sales drop, or we run into a three-foot rattlesnake, our brains go into hyper-drive, focussing our complete attention on the task at hand and evaluating it for risk.

In other words, without a change, there is no story.

Kenn Adams‘ Story Spine demonstrates the concept brilliantly.

Once upon a time

Every day…

Then one day…

And because of that…

And because of that…

Until finally…

And ever since then…

“Then one days” separate stories from other narrative forms. They represent the “uh-oh” moments that compel our meaning-seeking brains to assess the situation for risk and danger. Without “then one days,” we have no story. Rather, we have a rhetorical collection of facts.

Every story needs a rattlesnake–the “then one day” that transforms a humdrum routine into a troublesome scene. Therefore, the next time you want to deliver a message through a story, start by finding your rattlesnake.

by Ron Ploof | Apr 25, 2016 | Business Storytelling

“I’m sorry, Sir,” the grim-looking restaurant manager said to me. “We have a little problem.” An awkward nod from our waitress confirmed his statement.

“Somehow we dropped your credit card into the toaster,” the manager said, before presenting a plate containing a charred potato chip engraved with my name and sixteen digit number.

The acrid scent of burnt plastic wafted from the kitchen.

“Of course, we’re gonna to comp your breakfast, sir,” the manager said.

“Umm, yeah. Thanks,” I said.

Later that morning, I called the credit card company to request a replacement.

“What happened to the card?” the customer support rep asked. “Did you lose it?”

“No,” I said matter-of-factly. “Someone at the restaurant dropped it into the toaster.”

The rep laughed then caught herself. “I’m sorry for laughing, Mr. Ploof.”

“It’s okay,” I said. “It’s actually pretty funny. You can’t make stuff like this up, ya know.”

She chuckled in agreement.

As we wrapped up our conversation, the rep said, “Mr. Ploof, at the end of every week, the team gets together to tell our favorite customer stories. I just want you to know that this week–you’re mine.”

The best business stories are found in little moments like these. They’re the raw ingredients for pure story gold. However, are you mining for them? Has your company made story-mining a priority? Do you encourage your staff to recount their favorite (or least favorite) moments of the week? If not, give it a try. Not only will the team bond over similar experiences, but the company will also gather potential stories to build upon.

Lastly, write these story-starters down. There’s no need to develop them completely–that’s what your writers are for. Just document the highlights. Your professional storytellers can develop them into full-blown stories at a later time.

by Ron Ploof | Apr 18, 2016 | Business Storytelling

Last Tuesday, I had the pleasure of speaking to a group of entrepreneurs at the Draper University of Heroes. During Q&A, one asked if I had any suggestions for pitching highly technical products. He explained that the sophisticated nature of his product made it difficult to describe to people outside of his niche industry.

“I know exactly how you feel,” I said and described a similar situation that I once found myself in.

A gyroscope is a device that measures rotation in things like planes, boats, or spacecraft. My boss had asked me to summarize the concept behind a new device called the Hemispherical Resonator Gyroscope (HRG).

Surprisingly, the fundamental principle behind the HRG wasn’t discovered in some modern, high-tech research laboratory. A professor found it in the late 1800s after noticing that his wine glass behaved oddly as he spun around in his barstool. (Yeah, you can’t make this stuff up.) Evidently, after he flicked the rim with his fingernail, rather than propagating a pure tone while he rotated, professor G.H Bryan heard “beats.” So, he took his wine glass back to his lab to find out what was going on.

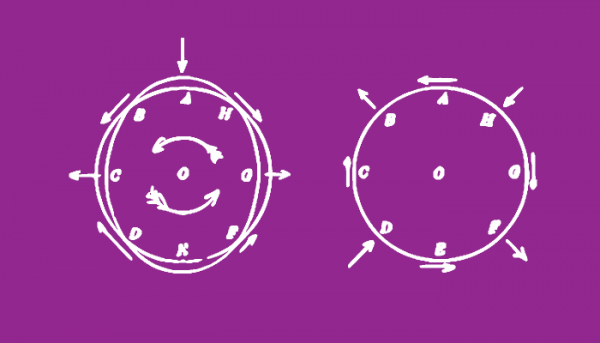

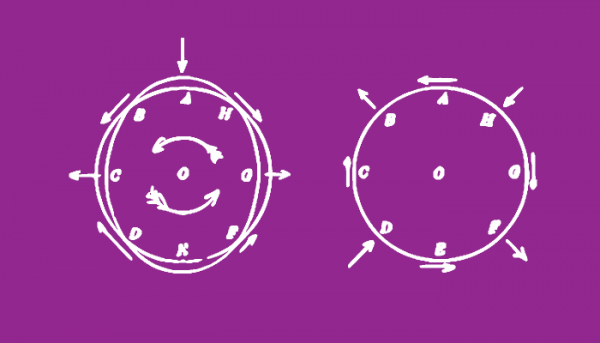

The animation at the bottom of this post illustrates how the rim of a wine glass bends and flexes while it rings. The professor noted that four parts of the rim barely moved (nodes) while four others (antinodes) move the most. He postulated that the “beats” that he heard resulted from the nodes traveling at a different angular rate than the bar stool. Therefore, if his theory proved true, the phenomenon could be used to build a gyroscope that calculates the angular rotation of the barstool—err—spacecraft, by simply monitoring the locations of the nodes.

The concept was simple enough, but I struggled with how to actually demonstrate it in front of a large audience. You see, it was 1986. Animated GIFs didn’t exist yet. Heck, PowerPoint wouldn’t be released for another year and even if it did, how could I animate through a carousel slide projector or an overhead projector?

I needed a prop—something that was both flexible enough to demonstrate nodes and antinodes and big enough for the whole room to see. I needed a Hula Hoop.

And so there I was, a 23-year-old electrical engineer, standing in front of an audience, bending and flexing a Hula Hoop over my head to simulate the rim of a ringing wine glass.

When I finished my story, I looked at the student who’d just asked for my advice. “You just need to find your Hula Hoop,” I said.

He smiled brightly. “Thank you. That’s very helpful.”

And off he went…to find his Hula Hoop.

Notes:

On the Beats in the Vibrations of a revolving Cylinder or Bell by G.H. Bryan, MA, St. Peter’s College. Cambridge. 1890.

by Ron Ploof | Apr 11, 2016 | Business Storytelling

One of the most common questions that people ask me is, “Where can I find business stories?” I’ve written extensively on this subject in blog posts such as:

Most of the methods mentioned in these articles rely on a storyteller’s observation skills and the ability to find patterns where others don’t. But, what if these human ways of finding stories aren’t feasible?

Take Big Data for example. According to IBM, “Every day, we create 2.5 quintillion bytes of data — so much that 90% of the data in the world today has been created in the last two years alone.” A quintillion is an unfathomable number to the human brain. It’s formed by placing a one before eighteen zeros. So, while Mount Big Data may be packed with potential stories, extracting them will require help. IBM has addressed this need by opening Watson Analytics to anyone willing to throw data at it. As a storyteller looking to upgrade his story-finding skills, I opened an account.

The hardest part of learning Watson Analytics wasn’t the tool; it was figuring out what data to process. Watson comes with “sample data,” but I learn best when applying new technologies to something that interests me. That’s when I thought of my favorite sport and wondered. “If I upload the Team Statistics from the 2015 NFL Season, could Watson unearth some story-starter nuggets that I couldn’t have found on my own?” In other words, what if I used Watson Analytics to find a Moneyball for football story?

It took me a few hours to create an Excel spreadsheet that contained over 160 stats for all 32 clubs. However, since the free version of Watson Analytics limits the amount of data to fifty categories, I was forced to whittle my massive spreadsheet down.

Watson’s “Predict” function took less than a minute to chew on 1,600 pieces of data (50 categories x 32 teams) and spit out “121 strong associations.” Although most were “No-duh!” obvious, such as Offensive Penalty Yards were positively correlated with Offensive Penalties and Total Rush Yards were positively correlated with Rush Attempts, one association stopped me in my tracks.

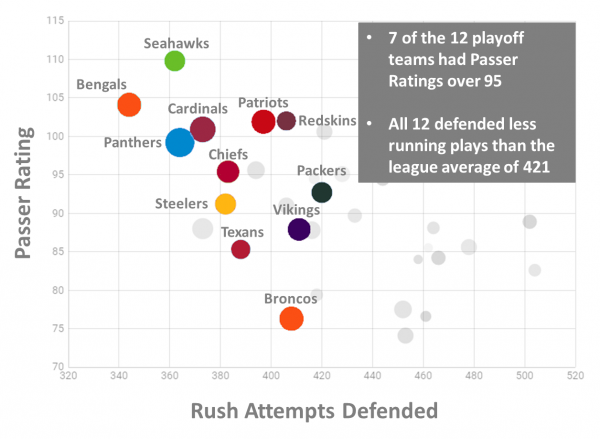

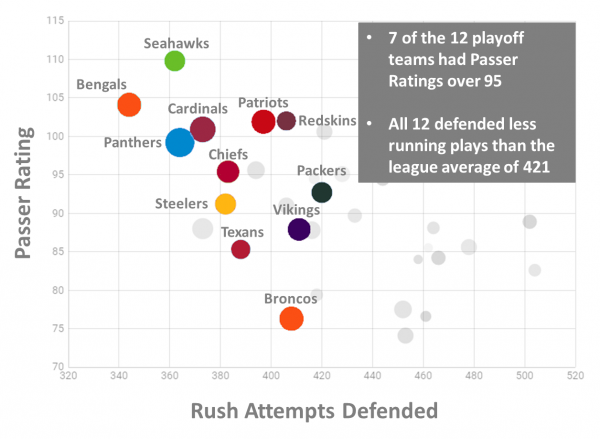

The correlation between number of Rush Attempts Defended and Passer Rating (r=0.60) is strong. As the number of Rush Attempts Defended increases, there is a strong tendency for Passer Rating to decrease.

This was exactly the type of counterintuitive correlation that I was hoping to find. The best data-inspired stories begin with Wait? What? questions and this potential association had me asking: “How could statistics about players who were never on the football field at the same time be related?”

The following chart illustrates the correlation between a team’s Passer Rating and the number of times that same team defends running plays.

The next chart highlights the twelve teams that made the playoffs in 2015. Note that all twelve defended less running plays than the league average of 421.

So, did Watson Analytics find a Moneyball for football stat? Maybe. We’d need to test the premise over more than one season to be sure. But either way, Watson did its job. It extracted the raw materials for a storyteller to begin processing into gold.

Does your business want to mine Big Data? If so, put tools like Watson Analytics into the hands of your business storytellers. Competitive advantages belong to enterprises that can find and tell unique data stories before anyone else.

Sources:

by Ron Ploof | Apr 4, 2016 | Business Storytelling

Two weeks ago, we defined a story as the result of people pursuing what they want. Let’s build upon that foundation to help you tell your next business story.

Business storytellers start with the following four questions:

- Who’s the person?

- What does the person want?

- What obstacles stand in between the two?

- How does the person choose to overcome those obstacles?

The answers to the first two questions are enough to create interest in the listener’s mind. The answers to the last two require strategy.

I’ve found that strategy is one of the most misused words. For some reason, many business folks use it to describe tactics. So, for the avoidance of doubt, let’s define strategy as a plan designed to overcome an obstacle while tactics are the specific tasks that must be completed to execute that plan.

There are an infinite number of tactics and a handful of strategies. According to Sun Tsu, the author of the 2,500-year-old The Art of War, there are only five strategies, also known as the five “Fs”: Frontal, Fortress, Fragment, Flank, and Feign. A business storyteller must choose at least one as the reason for the protagonist’s (person) actions to overcome the obstacle.

1) Frontal Strategy

When faced with an 800-pound gorilla (the obstacle), it’s tempting to look the beast in the eye and deal with it head-on. Frontal strategies are used all the time in movie climax- scenes like when Superman battles Lex Luthor or Luke Skywalker lightsabre-dances with Darth Vader. We also see it in business, such as when Blu-ray went head-to-head with HD DVD and the FBI sued Apple to unlock an iPhone.

While audiences may delight in watching heavyweights duke it out, pitting strength versus strength comes with a caveat. Sun Tsu advises that frontal strategies require the user to have at least a 3:1 advantage over the gorilla. Without such an advantage, frontal strategies can have unfavorable results, such as in Alderaan vs. the Death Star or Napster vs. The Recording Industry Association of America.

2) Fortress Strategy

Sometimes a protagonist wants to be left alone, but a gorilla messes with the plan. Rather than dealing with the gorilla, the protagonist implements a fortress strategy and waits for the gorilla to give up. For example:

- The Three Little Pigs built a brick house and waited for the Big Bad Wolf to hyperventilate.

- Mohammed Ali leaned against the ropes and let his opponents wear themselves out as he Rope-A-Doped them.

- IBM reminded its customers that “Nobody ever got fired for choosing IBM.”

The five strategies can be divided into two categories: brains vs. brawn. The first two fall into the brawn category. The remaining three require a little more thought.

3) Fragment Strategy

Sometimes an obstacle is too big to take on as a whole, and the protagonist needs to break it into manageable pieces. For example, suppose our protagonist is a sales executive who must sell against the industry’s 800-pound gorilla. Rather than trying to sell into the competitor’s most visible accounts, the protagonist chooses to stay off the RADAR by nibbling on its smaller accounts. Or, rather than competing head-to-head with the competitor’s entire product line, the sales rep decides to pick-off weaker ones. By using a fragment strategy, the protagonist chips away at the competitor’s advantage over time.

4) Flanking Strategy

Life isn’t fair. Sometimes the rules of the game benefit the gorilla. It’s at times like these when the protagonist must change the rules via a flanking strategy.

5) Feign Strategy

The last strategy is the most cerebral of the five. It requires a protagonist to outthink the gorilla through deception or by setting a trap. Fein strategy implementations include:

- a wolf wearing sheep’s clothing

- a coach calling a trick play

- an army hiding in a Trojan Horse that’s offered it to its enemy as a gift

- sacrificing a piece on a chessboard

Give it a try. Identify the people, their wants, and obstacles. Then find a strategy that the protagonists will employ to pursue those wants. Do the protagonists have a three-to-one advantage to tackle the problem head-on or will they just hold on for dear life? Will the main character break the obstacle into smaller pieces, change the rules of the game, or use sleight of hand?

Use these questions to form the foundation for your next story.

by Ron Ploof | Mar 28, 2016 | Business Storytelling

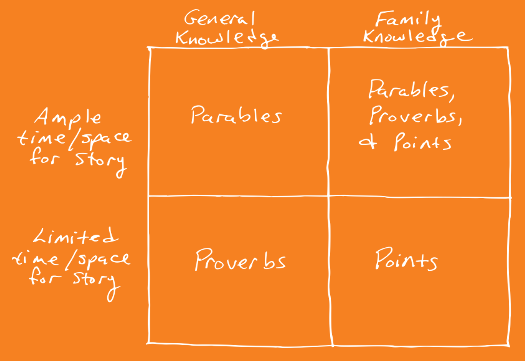

Business communicators use stories to convey knowledge. Most of the time, they’ll use a fully-developed parable with a strong beginning, interesting middle, and decisive ending. But, sometimes, everyday constraints don’t afford the use of a parable. Whether limited by the time required to deliver an elevator pitch or the number of characters allowed by a social network, business communicators must consider two other narrative forms: points and proverbs.

Unlike parables which can stand on their own, proverbs and points are dependent narrative forms. Each relies on a listener’s prior knowledge and experiences.

Proverbs

Proverbs are phrases encoded with knowledge. Although they present themselves as whimsical little sayings, proverbs deliver deep meaning to listeners as they reflect upon the symbols, metaphors and linguistic play that have been encoded into them.

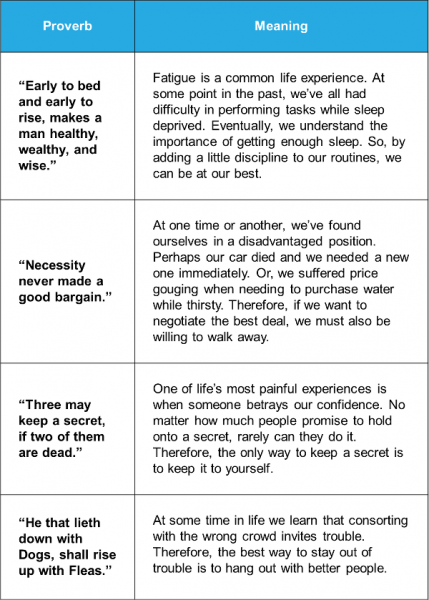

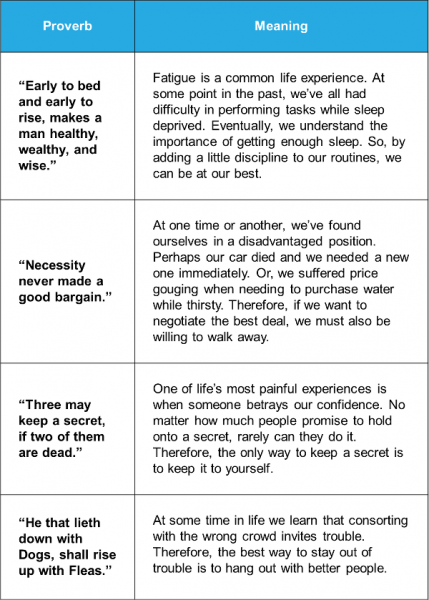

For example, let’s look at a few proverb examples from Ben Franklin:

The table demonstrates how proverbs encapsulate compressed knowledge. Franklin’s four proverbs contain 42 words, yet the explanations contain quadruple that amount. Proverbs are triple-threat communications vehicles because they’re memorable, repeatable and due to their universality, are frequently translated both to and from other languages.

Points

Points are another dependent narrative form. However, rather than relying on general prior knowledge to unpack new knowledge, points build upon highly specialized knowledge. Anyone with life experience can understand proverbs, yet only a small set of people can extract new knowledge from points.

Communicators who choose to use points must have an intimate understanding of their audience. Both teller and listener usually speak the same language and share common backgrounds. You’ve probably experienced point narratives when someone referred to an “inside joke” or said, “Sorry. You had to be there.” Point narratives are meaningful for insiders, yet lost on outsiders.

For example, take a look at the following excerpt from one of my old textbooks:

“Since solution of the error covariance equations usually represents the major portion of computer burden in any Kalman filter, an attractive way to make the filter meet computer hardware limitations is to precompute the error covariance, and thus the filter gain.”1

To most, this sentence is random gobbledygook. To a control theory engineer who eats, breathes, and sleeps covariance equations and Kalman filters, though, it’s a point that can be used to lighten the computational load of an onboard computer.

Story researcher Kendall Haven describes such communications as “family stories.”

“Your organization, your company, your department, your profession are all forms of “family.” Each of these professional families builds up tremendous amount of commonly held information (jargon, concepts, histories, definitions, acronyms, research, experiences, relationships, etc.)…Miscommunications and mistakes would reign supreme without them.”2

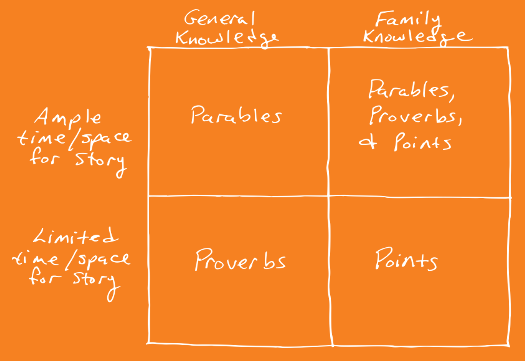

So, which knowledge delivery mechanism should you use in the future: a point, a proverb, or a parable? The answer depends upon two variables: time and the prior knowledge of your audience. Use this handy chart to determine which one you’ll use:

Let’s recap:

A point is a fragile knowledge seed that can only grow in the fertile ground of family knowledge.

A proverb is simple phrase that’s encoded with knowledge. Listeners use their own personal life experiences as the keys to unlock it.

A parable is a complete story that delivers new knowledge to general audiences through an entire arc.

The next time you need to convey knowledge, ask yourself two questions: How much time do I have and what do I know about the audience? By answering these two questions, you’ll be able to best determine whether you need parables, proverbs, or points.

Notes:

- Gelb, Arthur (1989). Applied Optimal Estimation (p. 230. ) MIT Press.

- Haven, Kendall (2014). Story Smart: Using the Science of Story to Persuade, Influence, Inspire, and Teach (p. 50). ABC-CLIO. Kindle Edition.