Business communicators use stories to convey knowledge. Most of the time, they’ll use a fully-developed parable with a strong beginning, interesting middle, and decisive ending. But, sometimes, everyday constraints don’t afford the use of a parable. Whether limited by the time required to deliver an elevator pitch or the number of characters allowed by a social network, business communicators must consider two other narrative forms: points and proverbs.

Unlike parables which can stand on their own, proverbs and points are dependent narrative forms. Each relies on a listener’s prior knowledge and experiences.

Proverbs

Proverbs are phrases encoded with knowledge. Although they present themselves as whimsical little sayings, proverbs deliver deep meaning to listeners as they reflect upon the symbols, metaphors and linguistic play that have been encoded into them.

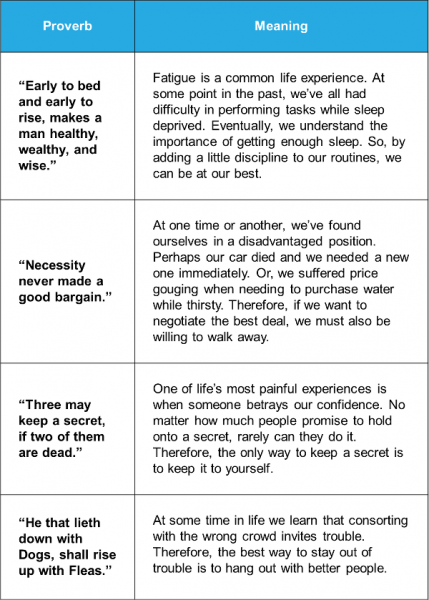

For example, let’s look at a few proverb examples from Ben Franklin:

The table demonstrates how proverbs encapsulate compressed knowledge. Franklin’s four proverbs contain 42 words, yet the explanations contain quadruple that amount. Proverbs are triple-threat communications vehicles because they’re memorable, repeatable and due to their universality, are frequently translated both to and from other languages.

Points

Points are another dependent narrative form. However, rather than relying on general prior knowledge to unpack new knowledge, points build upon highly specialized knowledge. Anyone with life experience can understand proverbs, yet only a small set of people can extract new knowledge from points.

Communicators who choose to use points must have an intimate understanding of their audience. Both teller and listener usually speak the same language and share common backgrounds. You’ve probably experienced point narratives when someone referred to an “inside joke” or said, “Sorry. You had to be there.” Point narratives are meaningful for insiders, yet lost on outsiders.

For example, take a look at the following excerpt from one of my old textbooks:

“Since solution of the error covariance equations usually represents the major portion of computer burden in any Kalman filter, an attractive way to make the filter meet computer hardware limitations is to precompute the error covariance, and thus the filter gain.”1

To most, this sentence is random gobbledygook. To a control theory engineer who eats, breathes, and sleeps covariance equations and Kalman filters, though, it’s a point that can be used to lighten the computational load of an onboard computer.

Story researcher Kendall Haven describes such communications as “family stories.”

“Your organization, your company, your department, your profession are all forms of “family.” Each of these professional families builds up tremendous amount of commonly held information (jargon, concepts, histories, definitions, acronyms, research, experiences, relationships, etc.)…Miscommunications and mistakes would reign supreme without them.”2

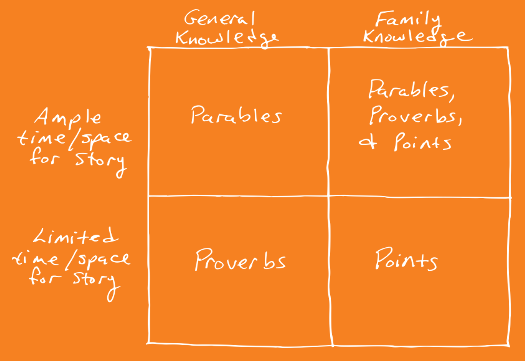

So, which knowledge delivery mechanism should you use in the future: a point, a proverb, or a parable? The answer depends upon two variables: time and the prior knowledge of your audience. Use this handy chart to determine which one you’ll use:

Let’s recap:

A point is a fragile knowledge seed that can only grow in the fertile ground of family knowledge.

A proverb is simple phrase that’s encoded with knowledge. Listeners use their own personal life experiences as the keys to unlock it.

A parable is a complete story that delivers new knowledge to general audiences through an entire arc.

The next time you need to convey knowledge, ask yourself two questions: How much time do I have and what do I know about the audience? By answering these two questions, you’ll be able to best determine whether you need parables, proverbs, or points.

Notes:

- Gelb, Arthur (1989). Applied Optimal Estimation (p. 230. ) MIT Press.

- Haven, Kendall (2014). Story Smart: Using the Science of Story to Persuade, Influence, Inspire, and Teach (p. 50). ABC-CLIO. Kindle Edition.