by Ron Ploof | Dec 12, 2016 | Business Storytelling

The car inched forward in rush hour traffic. It would be at least a half-hour before I reached Mineta San José International Airport. An elephant figurine on the dashboard caught my eye. “Who’s that?” I asked my Uber driver.

“That’s Ganesha,” Narayan said. “Where I come from, he’s the god of good luck.”

“Where are you from?”

“Nepal.”

“Roman Catholics consider St. Christopher the patron saint of travelers,” I said. “My grandmother always carried a St. Christopher medal in her car.”

“We all need a little luck,” he said.

“Yes we do. So, how long have you been in the states?” I asked.

“About five years.”

“What made you want to come here?”

“I grew up hearing how America was the land of milk and honey. All you had to do was land at an airport and choose from all of the Help Wanted signs in the windows. So, I saved some money and came here with a friend.”

Narayan appeared to be in his mid twenties. I mentally subtracted five years from this approximate age to picture an image of two, starry-eyed teenagers in a futile hunt for invisible Help Wanted signs.

“And how’d that work out for you?” I asked.

He glanced at me sheepishly. “Not well. We landed in Dallas. The airport was huge! I’d never seen an airport that big before. There were no Help Wanted signs anywhere. We figured that the signs were outside of the airport, so we got into a cab.”

“Where exactly did you tell the cabbie to go?”

“To where the Help Wanted signs were,” Narayan said matter-of-factly. “The taxi driver thought we were crazy.”

“I can’t imagine why,” I said.

“By the time we left the airport, we knew we were in trouble. We’d come halfway around the world, didn’t know anybody, didn’t have much money, and had no place to stay, ”

“So, what did you do?” I asked.

“I called my mother.”

I chuckled. “By far the best decision you’ve made yet.”

“She asked if our taxi driver was from Nepal. He wasn’t. He was from Pakistan. She said, ‘Good. Ask him if he knows any taxi drivers from Nepal.’”

“Wait!” I interrupted. “THAT was her plan?”

Narayan nodded. “The taxi driver called a friend, explained our situation, then drove us to this home. We lived with that Nepali taxi driver until we found jobs and a place to live.”

I stared at Narayan slack jawed. “Let me get this straight. You left Nepal with very little money and a plan to find a job upon landing in Dallas. When you didn’t see any Help Wanted signs, a Pakistani taxi driver took you to his Nepali friend who let you live with him until you could land on your feet?”

He shrugged his shoulders. “Yes.”

“Narayan, you’re the luckiest person that I’ve ever met.”

He pointed to the dashboard. “That’s why I carry Ganesha.”

by Ron Ploof | Dec 5, 2016 | Business Storytelling

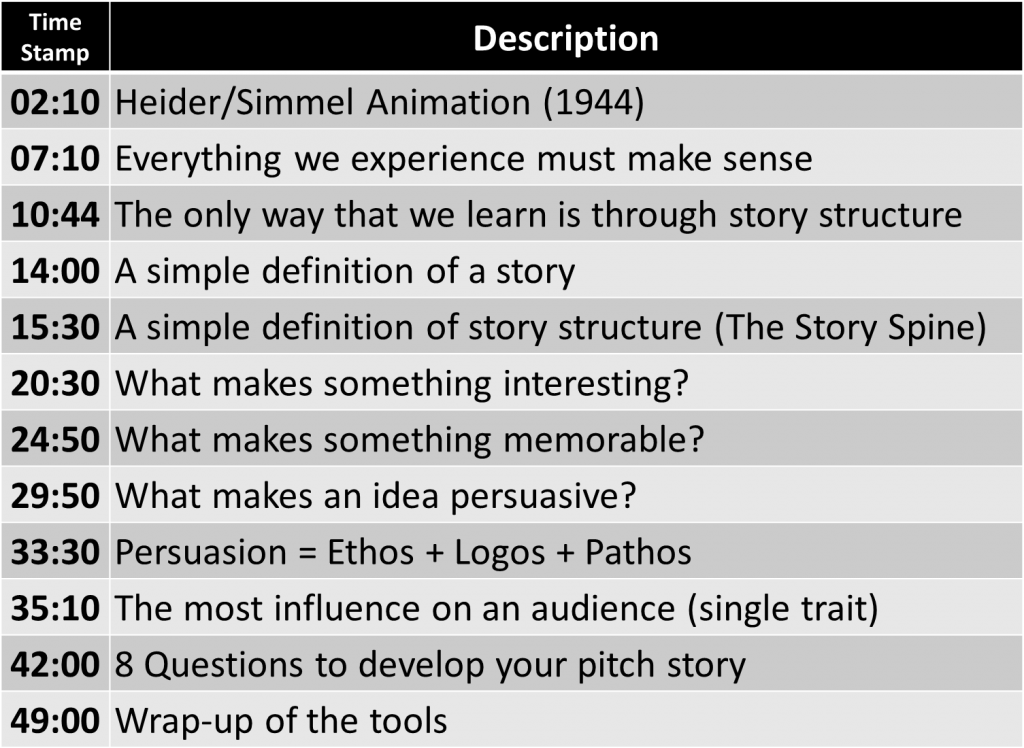

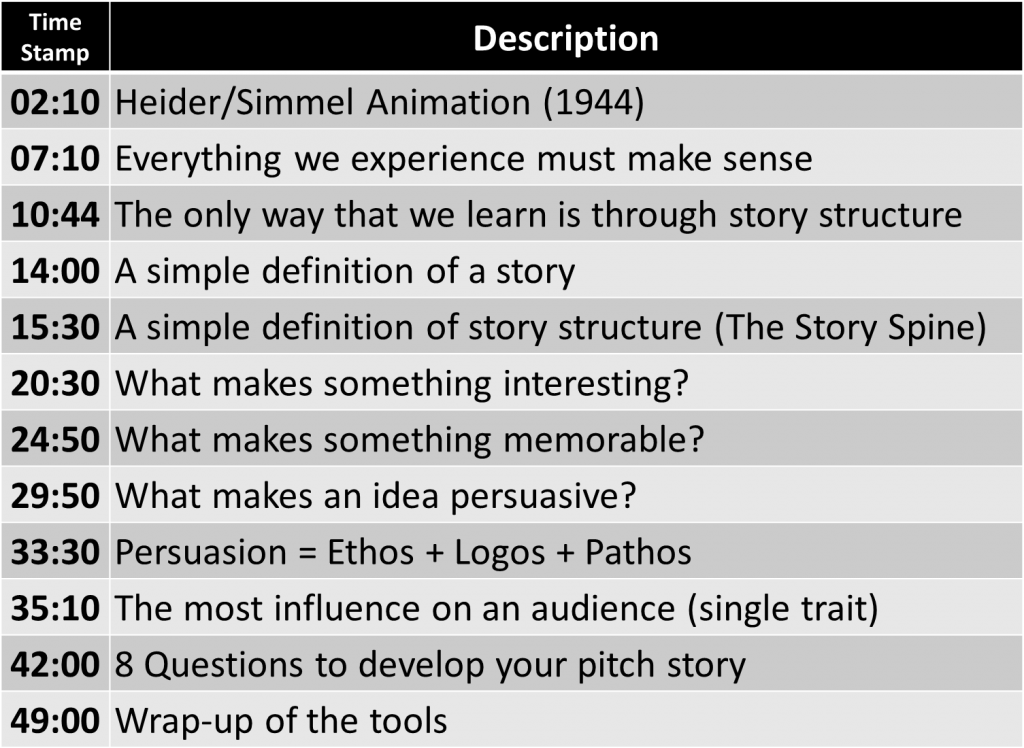

Graduation Day at Draper University is different than most schools. Rather than being purely ceremonial, the school’s entrepreneurial students actually take their final exam by pitching their companies to an audience of Silicon Valley investors. I’ve spoken at Draper twice this year to teach these budding entrepreneurs how to incorporate storytelling techniques into their pitches.

Last week, Draper published a recording of one of my talks called, How to Make Your Pitch Interesting, Memorable, and Persuasive. It’s 54 minutes long, so I’ve also provided time stamp information to help you find specific parts.

Credits:

by Ron Ploof | Nov 28, 2016 | Business Storytelling

Last spring, I had an opportunity to watch twenty-five entrepreneurs pitch their companies to Silicon Valley investors. The experience felt like a controlled experiment of sorts because each presentation sought the same goal (investment) and had the same amount of time to do so.

Watching these presentations serially helped me see patterns. Most of them ended on the dot, indicating that the entrepreneurs had practiced fitting their content into the allocated time. The second pattern was a bit more troubling. The majority of the presentations fell into the March category, meaning that they came in like a lion and went out like a lamb. These entrepreneurs had succumbed to a common pitfall; they wrote their stories in the order that they had planned on telling them, putting too much emphasis on the beginning and not enough on the ending.

StoryHow PitchDeck Card #17, Ending, offers the following advice for March stories:

“While most stories are told from the beginning to end, they’re written the other way around. Business storytellers begin with the story’s ending, then plot an intentional course toward it.”

Stories with strong openings and weak endings are buzz-kills because they set an audience’s expectations too high. With no way for the message to live up to the hype, the audience is left hanging. They feel cheated. Narratus interruptus.

Avoid creating March stories by spending just as much time on your story’s ending as on its beginning. Do so by asking questions like:

What’s the moral of this story?

What do I want the audience to do?

What do I want them to remember?

Consider creating a memorable catchphrase for them to take away…

…something like, Storytellers begin at the end. 🙂

Photo Credit: [Children in Race Crossing Finish Line]. [Between 1909 and 1923] Image. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/npc2007018638/.

by Ron Ploof | Nov 21, 2016 | Business Storytelling

I once had a sales manager who hated software product evaluations because they failed to deliver what they promised: a logical way of choosing a product.

For example, let’s say that a company is trying to decide between using Microsoft Office and Google Docs. The first thing that upper management might do is organize a task force–a fancy way of making a boring committee sound sexy. The committee…err task force…creates a list of requirements and then evaluates each product against them. Theoretically, all the task force needs to do is tally up the check marks and declare a winner.

But theory and reality rarely align. Milt explained that this type of analysis inevitably ends in a tie because each product will satisfy most of the requirements. Therefore, with no clear winner, the task force must figure out a way to break the tie. How do they do it? According to Milt, the most common way is to add a new column called “intangibles,” that may have items like this:

- Do we need to retrain our staff?

- Must we change the way we do things?

- How much effort will it take to convert our old files into the new format?

Milt understood that all purchases (B2B or B2C) are made on emotion and justified with logic. We like the way a new car makes us feel. We resist change. We’ve had great food at greasy spoons and mediocre ones at expensive restaurants. We live for the intangible aspect of our lives.

Storytellers are intangibles experts. They understand that major plot swings pivot on the tiny nuances instead of the biggest of facts. Intangibles cause listeners to think differently about a subject. They deliver more meaning than we expected. Intangibles pull listeners into a story because the majority of the human experience is spent in the fuzzy margins as opposed to the crisp letters of a page.

Storytellers seek intangibles. Which ones are waiting to be discovered in your story?

Photo Credit:

Harris & Ewing, photographer. [Man Using Microscope in Laboratory]. [1936] Image. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/hec2013010789/

by Ron Ploof | Nov 14, 2016 | Business Storytelling

If you’ve been reading the StoryHow blog from the very beginning, you’ve read 87 different articles about how to tell a story. But what about the practice of storytelling–actually using these tools to tell a complete story?

I’ve been a storyteller much longer than I’ve taught storytelling. I’ve been producing stories since 1991 when I released a two-hour audio cassette (yes, magnetic tape!) about the beginning of the American Revolution. In 1995, I wrote a novel that taught non-fiction economic lessons. And in 2005, I launched Griddlecakes Radio, which today is one of the world’s longest-running storytelling podcasts. The StoryHow method didn’t just happen. It’s the result of a lifetime of practice.

So, I’ve decided to mix it up a little today. Rather than writing about a particular StoryHow element, this 88th StoryHow post contains a completed audio story called USS IOWA: Three Generations One Story. Take a listen. Perhaps you’ll recognize some StoryHow elements?

There are two ways to listen. Either hit the orange play button to listen immediately or download the MP3 file through the download arrow.

by Ron Ploof | Nov 7, 2016 | Business Storytelling

My Dad hates the flavor of orange candy. So, why did he carry a pack of orange-flavored Lifesavers in his shirt pocket when he was a teenager? Why did he force himself to suck on the wretched-tasting things? It’s because of the story he told himself.

My wife is a home health care nurse. She’s always telling me stories of non-compliant patients–people who for one reason or another, refuse to heed medical advice. Whether it be someone with diabetes who ignores nutritional guidelines, a heart-attack victim that returns to a stressful job prematurely, or a surgery patient who refuses to stay in bed, non-compliant patients refuse to do what they are told. Why? Because of the stories they tell themselves.

We all tell ourselves stories. We do it every minute of every day as we evaluate the world around us. We ingest information, compare it with our prior experiences and make assumptions. The stories we tell ourselves form the foundation of our beliefs–independent of whether those beliefs are actually true or not.

“I’m feeling good today, so I can have that ice cream sundae.”

“I thrive in stressful environments. It’s actually good for me.”

“I’ve always been a fast healer. It’s okay for me to walk weeks before the doctor thinks I should.”

The best communicators understand that their audiences tell themselves stories. They work hard to ensure that the story they tell is actually the story being heard. But the flip side is also true. The worst communicators assume that the story they tell is the same one being heard. Therefore, they run the risk of message-misalignment, similar to the false conclusions of noncompliant patients.

My Dad broke his ankle while playing High School basketball. During one of his checkups, the doctor asked about the pack of cigarettes in his shirt pocket. While Dad stumbled his way through some lame justification, the doctor produced a picture of the inside of a human lung. He described alveoli, the tiny little sacks that were responsible for exchanging of oxygen and carbon dioxide. He said that if all of the alveoli were spread over a flat surface, that they’d fill a tennis court. Healthy alveoli, he said, were pink. Yet Dad’s smoking habit was turning them black as he clogged them with tars. Therefore, the doctor posited, the more Dad smoked, the less oxygen could enter his bloodstream, and ultimately hurt his abilities as an athlete.

The doctor’s story impacted my father so much that he never smoked again. He just needed help with the inevitable cravings. Dad needed his own story–a reminder of how bad cigarettes were.

And so he began carrying a package of orange-flavored Lifesavers.

Photo Credit: Detroit Publishing Co., Publisher. A Patient, Brooklyn Navy Yard Hospital. [Between 1890 and 1901] Image. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/det1994001130/PP/.