by Ron Ploof | Feb 8, 2016 | Business Storytelling

The hardest part of writing a story isn’t deciding what to add–it’s deciding what to subtract. No writer gets it right the first time. There’s always something to rearrange, combine, or tweak. Every story needs a little nip, tuck, or sometimes wholesale amputation.

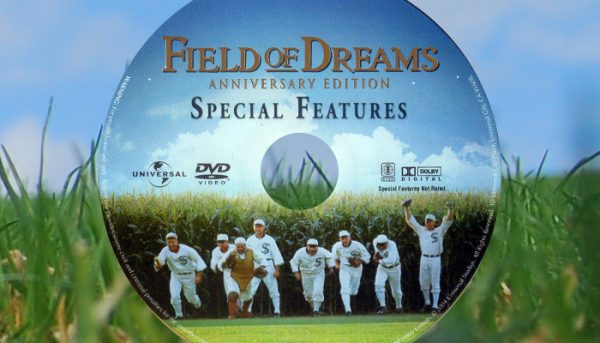

But, how does a storyteller determine what stays and what goes? What’s the thought process behind story editing choices? I found answers to such questions in a delightfully unexpected place: a DVD’s bonus features.

I had just finished watching the movie Field of Dreams and found myself longing for a little more, “If you build it, he will come.” As I returned the movie’s disc to its case, I noticed a second one labeled, “Field of Dreams Anniversary Edition Special Features.” Two of its table of contents entries sounded interesting:

- Deleted Scenes: Newly discovered and never-before-seen

- Bravo’s From Page to Screen: Field of Dreams A 48-minute documentary on making W.P. Kinsella’s novel, “Shoeless Joe”, into a film.

I found this resource especially useful because of a rare combination: Phil Alden Robinson played the role of screenwriter and director. The fact that the same person converted a dense, 250-page book into a scant 100-page screenplay, and then cut 200 hours (400,000 feet) of film into a one-hour-forty-minute feature length film, offered an unique story-editing perspective.

Robinson explained that Shoeless Joe was the only book that he’d ever read in one sitting, actually staying up all night until he finished it. However, he also explained how his love for the book hurt his efforts to adapt it. At one point, so guilt-ridden over his story-surgery, Robinson wrote an apology to W.P. Kinsella. While W.P. appreciated the sentiment, he congratulated Robinson on a beautiful adaptation.

“There were scenes in this book that I refer to as cul de sacs,” Robinson said, “things that didn’t advance the plot. Those were the first things that I cut. The world’s oldest living Cub. The twin brother. And so you have to be ruthless. I just felt–I gotta move those aside and focus on Ray’s story. How does Ray get from the beginning to the end?”

The “Deleted Scenes” chapter is particularly valuable for those familiar with the movie. The ability to see how those scenes would have changed the movie offers a front row seat in the editing bay. For example, Robinson admitted that the only reason one scene existed was to make the audience laugh. He cut it because they didn’t need a laugh at that time in the movie. Or, describing why one scene didn’t make it, he said, “It was actually a very nice little scene, but again when we cut the film together, we realized that we just didn’t need it. We wanted to kind of move the story forward.”

But Robinson’s most impactful insight came from his brutal self-honesty.

“As with any movie, there are a lot of scenes you shoot that don’t wind up in the final cut of the film…There’s a reason that all of these are in the script and a reason why all of them are out of the movie…because either they’re not written right or they weren’t directed right and so I’ll cop to the problem.”

Robinson’s honest self-assessment reminds us that the story isn’t about beautifully written words or stunning scenes shot at Magic Hour. It’s about serving the audience. Identifying cul de sacs and moving the story along requires story creators to put their egos aside and make painful choices.

So, are you looking for some inspiration for your own business story editing? Wipe the dust off of a favorite DVD and look for its “Special Features.” It just might open a window into the mind of a story editor.

Sources used in this post:

Field of Dreams. DVD. Directed by Phil Alden Robinson. 1989; Universal City, CA: Universal Studios, 2004

by Ron Ploof | Feb 1, 2016 | Business Storytelling

Last week, I analyzed a tech company’s digital marketing and found a common problem: its writers cram too much information into the corporate content. I found white papers packed with numerous features, blog posts with multiple topics, and press releases overflowing with superlatives. And while these digital missives basked in the warm approval of upper management, the decision to mix essential and nonessential information had a dangerous side effect–it transferred the burden of determining the differences between them to the audience. As we’ve seen in prior posts (Why You Need to Know About the Neural Story Net and Why Business Storytellers Must Mind The Gap), this is not a winning strategy.

Our responsibility as business communicators is to convey meaning. To do so, we must carefully choose each element that we’ll use to communicate that message. Unfortunately, many marketers and PR folks abdicate that responsibility and create bloated pieces overflowing with facts, specs, and mind-numbing hyphenations like award-winning, best-in-class, mission-critical, high-value, and out-of-the-box.

So, what can we do about it? How can we determine which elements to keep and which ones to edit out? I like to use Chekhov’s Gun.

“Remove everything that has no relevance to the story. If you say in the first chapter that there is a rifle hanging on the wall, in the second or third chapter it absolutely must go off. If it’s not going to be fired, it shouldn’t be hanging there.”

— Anton Chekhov

Although this century-old advice was intended for novelists, present day business communicators can use Chekhov’s gun to evaluate their informational choices. For example, if we say that our products replace legacy systems, then we better explain “how so” later in the story. If we describe a new feature as a revolutionary, then we had better talk about the casualties of said revolution. Every element in the story must be tested. If it plays no corresponding role later in the story, it needs to be eliminated…ruthlessly.

Cut to the chase. Make fewer points. Then use Chekhov’s gun to separate the essential elements from the nonessential ones. Essential elements are bulletproof. Nonessentials must be killed without remorse.

Photo Credit: Library of Congress

by Ron Ploof | Jan 25, 2016 | Business Storytelling

The little boy escaped his dad’s grasp and ran toward the restaurant’s revolving door. Three teenagers, who’d crammed themselves into one of its pie-shaped wedges, pushed hard—transforming a once harmless portal into aluminum jaws that closed rapidly on the little boy’s reaching arm. As the only person close enough to do anything about it, I found myself caught in a dilemma. Should I act on my instinct to protect the child or respect a social rule to never touch a stranger’s kid?

The teenagers pushed. The gap narrowed. And I had milliseconds to make a decision.

New business storytellers make a common mistake: they invest more time on a story’s roles and events than on the actual influences that shape them. And by shortchanging the things that drive character behavior, they also squander the best opportunity to impress their audiences.

Experienced business storytellers, though, understand the power of the throughline (StoryHow PitchDeck Card #40.). Throughline is a character’s motivation to accomplish a goal. It’s the driving force that remains constant throughout the entire story, independent of the obstacles that inhibit a character’s progress toward achieving that goal.

Story researcher Kendall Haven agrees. His experiments have revealed that one story element above all others has the most impact on an audience.

“When you use more powerful motives to turn a goal from a mere want to an absolute necessity, you instantly create audience interest, empathy, and support. Motives link directly to both the head and the heart of an audience.”1

I grabbed the boy’s jersey and pulled hard, causing the little guy to slide across the linoleum floor. The good news is that I’d successfully removed him from harm. The bad news is that I’d simultaneously placed myself into it, as his Mom locked her laser-like gaze onto the brute who’d just tossed her baby across the restaurant floor like a rag doll. Luckily for me, Dad saw the whole thing and intercepted mama bear before she could commence my mauling. While Mom struggled violently to break herself free of Dad’s bear hug, he looked at me and mouthed the words, “Thank you.”

Rather than risk my life on Dad’s ability to restrain the wiry woman, I lengthened my stride, spun through the revolving door, and sprinted toward the relative safety of my car.

There are always at least two stories: the one being told and the one being heard. In this example, two people saw the same event, yet interpreted them differently. Dad had enough knowledge of the situation to understand my motivation to protect. With only partial information, however, Mom could only assume something more nefarious.

So, what is your motivation as a business storyteller? Is it to be helpful? Is it to cram products down people’s throats? Now, take a step back and ask yourself, “Am I sure that the audience shares my view?” In other words, do they know your real motivation like the boy’s Dad, or are they assuming their own like his Mom?

Spend time developing the most important of all story elements: the throughline.

Notes:

- Haven, Kendall (2014-10-14). Story Smart: Using the Science of Story to Persuade, Influence, Inspire, and Teach (pp. 87). ABC-CLIO. Kindle Edition.

by Ron Ploof | Jan 18, 2016 | Business Storytelling

My grandmother once had a problem. No matter how hard she tried, she just couldn’t remember the difference between her right and left. And while being directionally challenged didn’t pose many problems while she was a young girl, her affliction needed to be resolved after she learned how to drive.

Her solution came from an unexpected source–her Roman Catholic upbringing. One day, she noticed that she always used her right hand while making the sign of the cross. Evidently, her conscious mind couldn’t remember right from left, but her unconscious mind did, and she’d stumbled upon a memory trigger. From that day onward, whenever she received directional information and needed to determine right from left, my grandmother would start to make the sign of the cross and then navigate appropriately.

We use memory triggers such as mnemonic rules and rhymes all the time:

- “i” before “e” except after “c” …

- 30 days hath September, April, May, and November…

So, it begs the question: Do story triggers exist? The answer is yes, but we need to study what makes things memorable first.

Every waking minute of every day, information from our five senses inundates our brains. We smell the coffee, hear it percolate, see it steam and feel its temperature until we finally taste it. We’ll drink that coffee with the morning news playing in the background while simultaneously checking email and waiting for the microwave oven to beep.

People are truly creatures of habit, but what do we remember about our routines? Not much, because for some reason, our brains ignore ordinary events.

Have you ever driven to work only to wonder how you got there? What happened? Did you lose consciousness? Were you asleep at the wheel? Of course not. You probably drove safely and obeyed all the traffic rules. Had that same commute included a flat tire, a fender bender, or a blinding snowstorm, however, you’d not only remember many of the details, but you’d also have a story to tell your coworkers.

Our minds look past sameness to find differences, giving contrast an unfair advantage over our memories. Rather than remembering everyday experiences, we recall atypical transitions into and out of them. Trigger words like first and last, help us recall our first job, first car, first date, and first kiss. If we haven’t seen someone for a very long time, it’s common to ask, “When was the last time we saw one another?”

Therefore, since our memories live at the edges of change, that’s where we should look for our stories. Business storytellers use trigger words–words that live at the edge of change–in two different ways:

1. Drawing stories out of clients. Most clients freeze up when asked for their stories, mistakenly assuming that they have no stories to tell. However, storytellers know that a few carefully chosen trigger words can prompt those same clients into telling stories about the best decision they’ve ever made, the worst customer they’ve met, the first time they tried a new approach or the last time they visited a customer.

2. Hooking an audience. Great storytellers know that humans bond through shared experiences. They use trigger words to get audiences to lean forward. For example:

- “The first time that I…”

- “The last time that we…”

- “The best example of…”

- “The most embarrassing moment of my life was when I…”

Listeners and storytellers bond over trigger words because we’ve all had firsts, lasts, bests, and worsts. And more importantly, listeners know instinctively that good stories reside on the other side of them.

So, are you searching for a story to tell? Use trigger words to spark memories:

- most and least

- best and worst.

- highest and lowest

- biggest and smallest

- firsts and lasts

I bet you’ll uncover many stories that your audience can relate with.

by Ron Ploof | Jan 11, 2016 | Business Storytelling

The goal of any business story is to convey meaning. The storyteller’s challenge is to mind the gap between the story being told and the one that’s being heard. To understand this gap, we need to take a closer look at story structure.

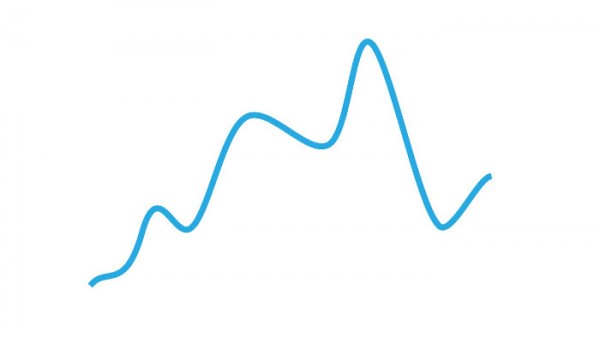

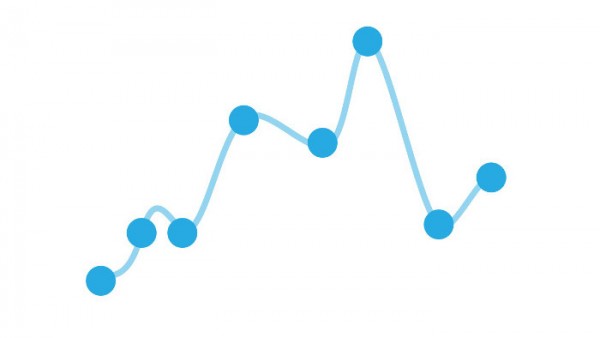

Stories depicted graphically are typically shown as continuous paths that have a beginning, a curvy middle, and an ending that represents change.

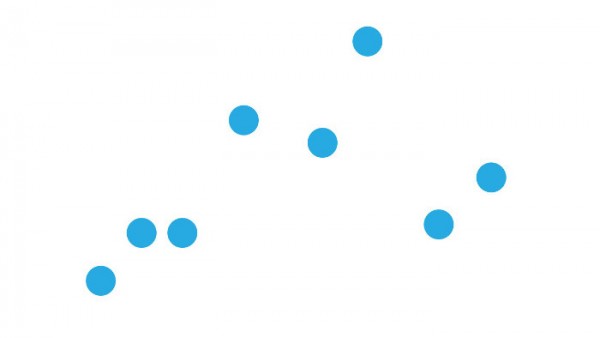

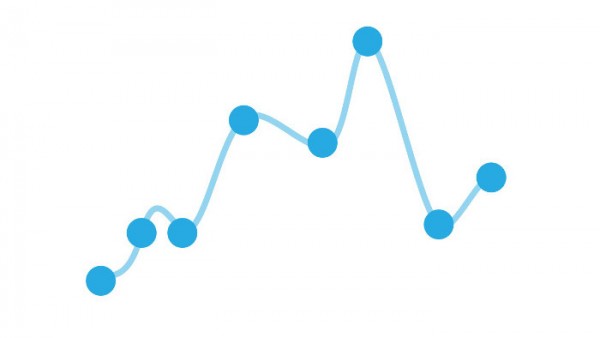

But stories aren’t continuous. Instead, they consist of the discrete pieces of information that were chosen painstakingly by a storyteller.

Any perceived continuity is a byproduct of the way that those pieces were connected inside the listener’s mind.

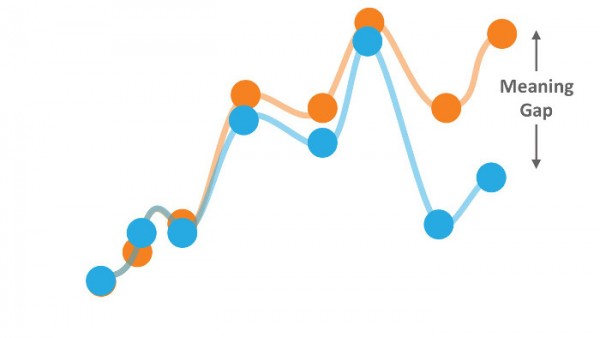

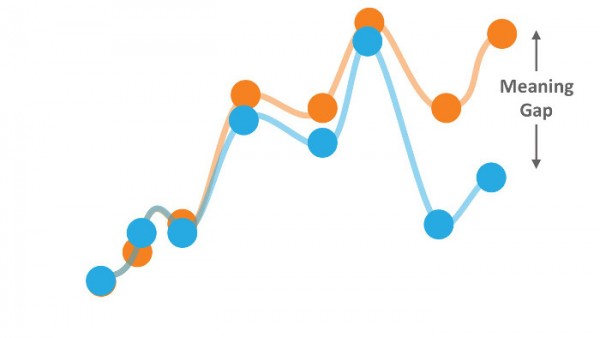

Storytellers understand that two roles are required in the telling of a story: the person that creates the dots and the one who connects them. If the storyteller chooses correctly, the meaning is conveyed with little or no distortion. However, if the storyteller misses the mark, the story bifurcates into two different stories: the one being told and the one being heard. The difference is called the meaning gap.

Most meaning gaps result as consequences of two critical storyteller choices:

- the when choice–that determines the timing of information delivery

- the what choice–that determines the type of information delivered

The When Choice

Great storytellers know how to deliver enough information to make their point while maintaining the audience’s interest. Too much and the story bogs down in details. Too little and the audience fails to see the relevance. Either way, though, the end result is the same—the audience zones out.

Over the years, I’ve noticed that the trend to deliver too much information comes from a lack of faith in the audience. With no confidence that the audience can connect the dots on their own, business communicators make choices to “dumb things down,” leaving nothing to chance and thus assuming both the role of dot creator and dot-connector. The problem with this strategy is that the listener cannot be removed from the equation. So, rather than leading the audience to some foregone conclusion, spoon feeding creates the unintended consequence of overwhelming the listener’s dot-connecting capabilities. The result? An intense urge to find stories elsewhere by checking their email, texting a friend, or liking a Facebook post.

Delivering too little information is just as bad. A storyteller who chooses to hand wave over vital story details risks listeners who fail to see the story’s relevance. Without an ability to connect the story to something that’s personally useful, listeners will seek their own stories by tuning out and checking Twitter.

The What Choice

Unfortunately, timing isn’t the only component affecting the meaning gap. If a difference exists between what the listener knows and what the storyteller is saying, listener’s will just morph the new information into something that’s consistent with their personal understanding.

You’ve seen this before. Have you ever explained something and the person you told said, “Yeah. I get it,” only to find that “it” had nothing to do with what you said? Or perhaps the person made a snap judgment, totally negating your point before you even had a chance to finish it? We all have internal biases that drive our understandings.

Do you prefer one political party over another? If so, think about how your prior knowledge has an unfair advantage over what you hear. Do you place a higher value on the ideas of people who share your beliefs? Are you more willing to cut those same folks some slack when they make a little mistake? Now, think about someone who has different views. Do you offer them the same liberties? Of course, you don’t. It’s human nature. Just remember that the next time you are preparing to tell a story. Ask yourself, “What is the audience assuming about me and what I’m about to say?”

Minding the Gap

So, how can a storyteller ensure a match between the story being told and the one being heard? Mind the Gap. Carefully modulate each story point with an understanding of the role of the listener. If you can help listeners see themselves in the story, the data, or the experience that you are trying to convey, they’ll be more likely to understand what you’re saying.

The secret is to learn as much about the audience’s prior knowledge as you can. Use that knowledge to help them build a platform of understanding. For example, when speaking to a homogeneous audience with specialized knowledge of your topic, feel free to use loftier concepts. They speak a common language, so you can forego the formalities. Yet, if your audience is more heterogeneous, thus lacking a foundational base by which to speak from, focus on the things that we share as humans. We all know what it’s like to feel pleasure or feel pain. We all know what it’s like to win and to lose. Use analogies that tie these common knowledge elements to your new ideas.

Mind the gap. Your audiences will appreciate following you along for the ride.

by Ron Ploof | Jan 4, 2016 | Business Storytelling

A long time ago, in a marketing department far, far away, I received the worst piece of writing advice ever.

“Replace all of your ‘buts’ with ‘ands’ because they sound nicer.”

For example, if I wrote something like:

“The simulator is fast, but it costs more than the competition,”

I was told to replace ‘but’ with ‘and’ to make:

“The simulator is fast and it costs more than the competition.”

Evidently, conventional marketing wisdom considers ‘and’ as the kinder and gentler conjunction.

ANDS Lead to Inclusion Stories

‘Ands’ probably sound nicer because they lead to inclusion stories which fuse two or more competing ideas together. Since these ideas are dependent upon one another, inclusion-story characters must address them as a single unit.

The best examples of inclusion stories come from improv and The Rule of Agreement. By responding to new story elements with “Yes and,” performers create delightful calamities that flourish with each new line. If the Rule of Agreement is broken with a “Yes but,” however, the resulting buzz-kill saps the story of its energy, limits story options, and ultimately sets the story on a narrowed path.

Inclusion stories are valuable tools for enterprises seeking innovative ideas because of the non-sequitur ideas and situations that they can spawn. They can set the basis for brainstorming or team building activities.

BUTS Lead to Exclusion Stories

Exclusion stories, on the other hand, allow for those same competing ideas to be handled as separate entities. Take the archetypal story of a protagonist who struggles against the efforts of the antagonist. The protagonist can deal with each obstacle that the antagonist presents separately, rather than collectively.

Let’s try an example. What if we compared inclusion and exclusion stories by imagining how the book JAWS would have turned out had Peter Benchley chosen to tell it each way.

The following dialog would initiate the beginning of an inclusion story.

Mayor Vaughn: “Amity needs more tourists at the beach.”

Chief Brody: “Yes, and there’s a big shark in the harbor.”

Since the rules of inclusion preclude the separation of the shark from a safe beach, the characters must seek an inclusive (Yes, and) solution. Perhaps Mayer Vaughn will open a shark-cage store, teach speed-swimming lessons, or develop a shark-repellent sunscreen (SPF 30 = Shark Proof Factor at 30 ft).

Now let’s look at JAWS as an exclusion story.

Mayor Vaughn: “Amity needs more tourists at the beach.”

Chief Brody: “Yes, but there’s a big shark in the harbor.”

The rules of exclusion allow the shark and a safe beach to be addressed separately. Therefore, Benchley seeks to eliminate the shark so that the good people of Amity can return to their carefree, beachgoing ways. Yet, each attempt to deal with the shark creates its own ramifications. First, Benchley chose to have Mayor Vaughn underestimate the risk of opening the beaches, thus leading to new and senseless shark attacks. Next he chose to offer a bounty, which resulted in amateur shark-hunters placing themselves into dangerous situations.

The storyteller plays a god-like role in exclusion stories, meticulously aligning each event and response onto a story path that leads to a final conclusion–just like in the business world.

Which brings us back to:

“The simulator is fast, but it costs more than the competition.”

Cost is a common business complication that sets up its own events and responses. A sales rep wants to discount the product. The finance manager, who’s compensated on corporate margins, doesn’t. Some customers will choose to pay the premium and others won’t. Perhaps those who chose the former accepted creative financing options. Or maybe they figured that since faster simulations shortened product development schedules, that the benefits of a faster time-to-market swamped the additional costs. Either way, exclusion stories have concrete and relatable endings.

Inclusion stories are rosy. Exclusion stories are thorny. And while most marketers lean towards the former, they shouldn’t ignore the latter. Therefore, before blindly replacing all ‘buts’ with ‘ands,’ explore both. At a minimum, you’ll have a better reason for your word choice than “it just sounded nicer.”

Extra Credit: Replace AND THEN with BUT or THEREFORE

In this video, Trey Parker and Matt Stone of the hit series South Park, offer the opposite advice of my old marketing manager. They suggest that whenever you see an “and then,” replace it with a “but” or a “therefore.”