The goal of any business story is to convey meaning. The storyteller’s challenge is to mind the gap between the story being told and the one that’s being heard. To understand this gap, we need to take a closer look at story structure.

Stories depicted graphically are typically shown as continuous paths that have a beginning, a curvy middle, and an ending that represents change.

But stories aren’t continuous. Instead, they consist of the discrete pieces of information that were chosen painstakingly by a storyteller.

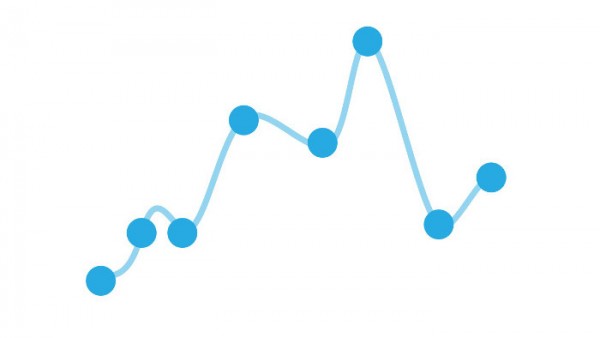

Any perceived continuity is a byproduct of the way that those pieces were connected inside the listener’s mind.

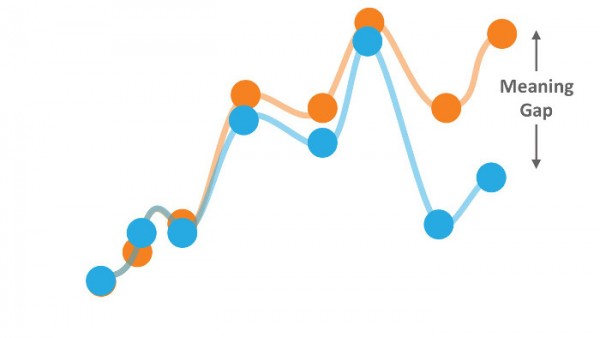

Storytellers understand that two roles are required in the telling of a story: the person that creates the dots and the one who connects them. If the storyteller chooses correctly, the meaning is conveyed with little or no distortion. However, if the storyteller misses the mark, the story bifurcates into two different stories: the one being told and the one being heard. The difference is called the meaning gap.

Most meaning gaps result as consequences of two critical storyteller choices:

- the when choice–that determines the timing of information delivery

- the what choice–that determines the type of information delivered

The When Choice

Great storytellers know how to deliver enough information to make their point while maintaining the audience’s interest. Too much and the story bogs down in details. Too little and the audience fails to see the relevance. Either way, though, the end result is the same—the audience zones out.

Over the years, I’ve noticed that the trend to deliver too much information comes from a lack of faith in the audience. With no confidence that the audience can connect the dots on their own, business communicators make choices to “dumb things down,” leaving nothing to chance and thus assuming both the role of dot creator and dot-connector. The problem with this strategy is that the listener cannot be removed from the equation. So, rather than leading the audience to some foregone conclusion, spoon feeding creates the unintended consequence of overwhelming the listener’s dot-connecting capabilities. The result? An intense urge to find stories elsewhere by checking their email, texting a friend, or liking a Facebook post.

Delivering too little information is just as bad. A storyteller who chooses to hand wave over vital story details risks listeners who fail to see the story’s relevance. Without an ability to connect the story to something that’s personally useful, listeners will seek their own stories by tuning out and checking Twitter.

The What Choice

Unfortunately, timing isn’t the only component affecting the meaning gap. If a difference exists between what the listener knows and what the storyteller is saying, listener’s will just morph the new information into something that’s consistent with their personal understanding.

You’ve seen this before. Have you ever explained something and the person you told said, “Yeah. I get it,” only to find that “it” had nothing to do with what you said? Or perhaps the person made a snap judgment, totally negating your point before you even had a chance to finish it? We all have internal biases that drive our understandings.

Do you prefer one political party over another? If so, think about how your prior knowledge has an unfair advantage over what you hear. Do you place a higher value on the ideas of people who share your beliefs? Are you more willing to cut those same folks some slack when they make a little mistake? Now, think about someone who has different views. Do you offer them the same liberties? Of course, you don’t. It’s human nature. Just remember that the next time you are preparing to tell a story. Ask yourself, “What is the audience assuming about me and what I’m about to say?”

Minding the Gap

So, how can a storyteller ensure a match between the story being told and the one being heard? Mind the Gap. Carefully modulate each story point with an understanding of the role of the listener. If you can help listeners see themselves in the story, the data, or the experience that you are trying to convey, they’ll be more likely to understand what you’re saying.

The secret is to learn as much about the audience’s prior knowledge as you can. Use that knowledge to help them build a platform of understanding. For example, when speaking to a homogeneous audience with specialized knowledge of your topic, feel free to use loftier concepts. They speak a common language, so you can forego the formalities. Yet, if your audience is more heterogeneous, thus lacking a foundational base by which to speak from, focus on the things that we share as humans. We all know what it’s like to feel pleasure or feel pain. We all know what it’s like to win and to lose. Use analogies that tie these common knowledge elements to your new ideas.

Mind the gap. Your audiences will appreciate following you along for the ride.