by Ron Ploof | Dec 17, 2018 | Proverbs

All written works consist of form and function. Since form is more complicated than function (see last post), we’ll need to spread our discussion about it across a few posts.

Proverbial form is split into two major pieces: frames (the structure by which we build our proverbs) and finishes (the techniques used to gussy ’em up). Today we cover frames.

Frames come in four categories: Metaphor/Definition, Comparison, Conditional, and Special

1. Metaphor/Definition

Metaphor is the building block of all proverbs, thus it deserves its own frame category. Proverbs built upon metaphor/definition frames include:

- time is money

- ignorance is bliss

- a diamond is forever

2. Comparisons

Comparison frames juxtapose certain roles, events, and influences to make a point. They frequently contain qualifying terms such as better, best and worse:

- It’s better to have loved and lost than have to have never loved at all

- Old friends and old wine are best

- False friends are worse than open enemies

3. Conditionals

Conditional frames establish situational advice. They typically contain setup words like if and when:

- If the shoe fits, wear it

- If you lose your temper, don’t look for it

- When EF Hutton speaks, people listen

4. Special Frames

And lastly, a subset of frames exists that may contain metaphor/definition, comparison, or conditional elements, but do so uniquely. There are two special frame subcategories: derivatives and implied.

4a. Derivative (Special)

Derivative proverbs are built upon well-established sayings and cultural references, thus they come spring-loaded with memorability. Many carry humor which lowers the barrier to listener adoption and increases the likelihood that the proverb will be repeated. My favorite derivative proverb results from the combination of two other proverbs:

A rolling stone gathers no moss + open mouth insert foot = a closed mouth gathers no foot

My storytelling buddy Park Howell used an iconic song as a derivative frame to form:

a spoonful of story helps the data go down

(Can’t ya just hear Julie Andrews singing it?)

4b. Implied (Special)

Finally, while all proverbs are based in metaphor and formed upon frames, sometimes those frames get eliminated during the editing process. For example, let’s take the proverb no pain no gain. Note the absence of telltales for comparisons (better/best/worse) nor conditionals (if/then/when). Does this mean that the proverb has no frame?

We’ll dive deeper into this topic when we talk about finishes, but proverb creators start with a big idea, determine a function and a frame, and then iterate through an editing cycle to make the proverb more memorable and repeatable. Sometimes this process eliminates telltales (better/best/worse/if/then/when) while simultaneously leaving behind cognitive references to them.

For example, perhaps the first incarnation of no pain, no gain read: If you want to gain, you must experience pain before some sharp copy editor chopped those nine words to four. And although the proverb lost its conditional telltale (if), cognitive frame references remain in the minds of both speaker and listener. The speaker implies the conditional frame while the listener infers it.

Now it’s your turn. Examine your favorite proverbs. Can you determine their functions and frames? The better you are at deconstructing existing proverbs, the better you’ll be with creating your own.

If you want to learn more about proverbs, grab a copy of The Proverb Effect on Amazon.com.

Photo Credit: Extension of library of Harvard College, Iron details. Ware and Van Brunt architects / Wm. C. Richardson, del. Cambridge Massachusetts, 1878. Boston: Heliotype Printing Co. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2007682661/

by Ron Ploof | Dec 2, 2018 | Proverbs

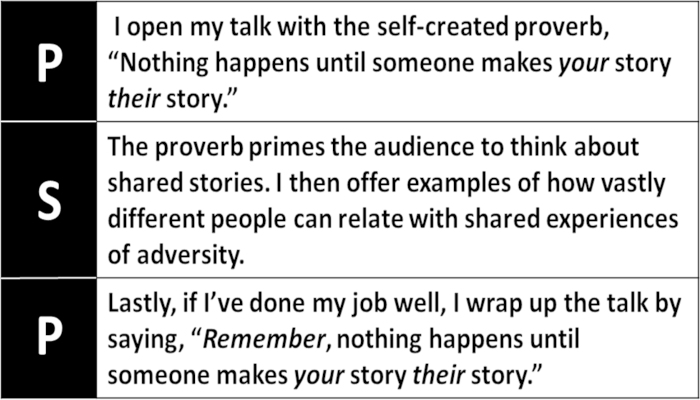

Last post, I described the StoryHow™ PSP method of building a talk. The technique has speakers open with a proverb, offer evidence via a story, and finally close with that proverb. While the same proverb is used to bookend the story, its purpose is different. The first instance acts as a premise and the second as a conclusion. In this post, I describe the first of a three part process for creating your own proverbs.

Whether you’re sharing an opinion, giving advice, or just leaving your audience with something to chew on, you first must make a choice. What are you trying to accomplish? What do you need your message to do? In the language of proverbs, you need to determine your function.

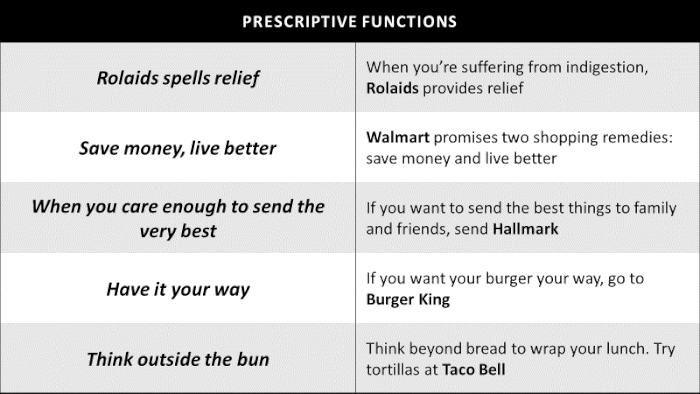

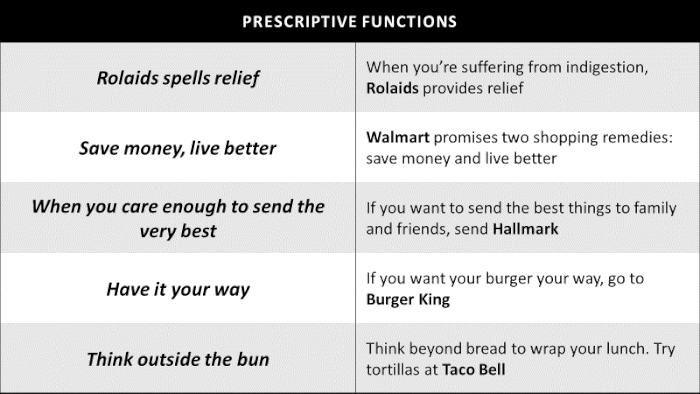

Proverb functions come in three forms: definitions, predictions, or prescriptions:

- Definitions describe one thing in terms of another. They typically contain words like is, are and like

- Predictions illustrate a cause and effect relationship to show how one event leads to another

- Prescriptions offer ways to either solve or prevent a problem

I’ve found that the best business taglines are proverbish, so let’s use a few to learn about the differences.

So, now it’s your turn. What’s your favorite business slogan? Can you determine it uses definition, prediction, or prescription?

If you want to learn more about proverbs, grab a copy of The Proverb Effect on Amazon.com.

Sources:

-

- https://superdream.com/news-blog/best-advertising-slogans

- http://examples.yourdictionary.com/catchy-slogan-examples.html

Photo Credit: Clarence H. White School Of Photography, Steiner, Ralph, photographer. Typewriter Keys. , 1921. , Printed 1945. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2004666344/

by Ron Ploof | Nov 12, 2018 | Business Storytelling

So, you have a big idea, need to share it with an audience, and are looking to structure your talk. How do you choose a beginning, middle, and end? Have you considered using the StoryHow™ PSP method?

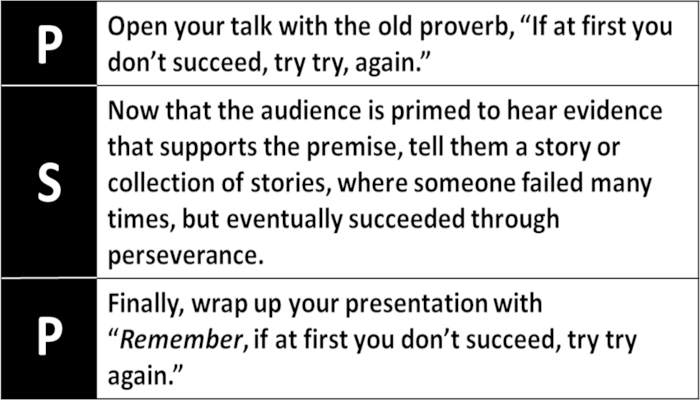

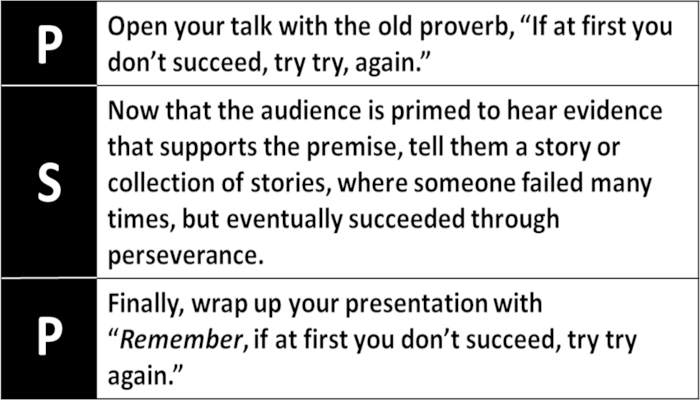

In my recent book, The Proverb Effect, I teach how old proverbs have helped teachers teach and students learn for thousands of years. Something in their linguistic structure gives proverbs the unique capability to act as both premise and conclusion. PSP uses this dual capability to open your talk using proverb as a premise, follow it with story-based examples, then wrap it all up by repeating the proverb as a conclusion. PSP helps you open and close strong.

For example, let’s use PSP to structure a talk about the power of persistence.

The method is effective because the human brain is comfortable listening to stories and proverbs are the ultimate long-stories short.

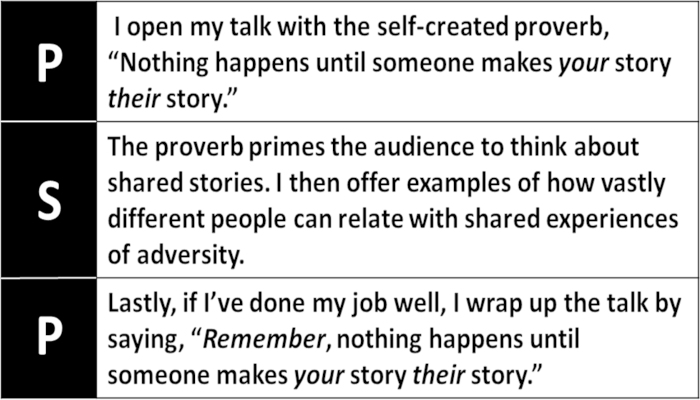

The first example used an old proverb, but perhaps you want to use one of your own. Here’s an example of one of my PSP talks.

Let’s say that I want to share the big idea that people will only join your cause if they can relate personally with it.

Give it a try. Use PSP to structure your next talk using the following steps:

- Convert that big idea into a proverb

- Open your presentation with it

- Offer evidence through stories

- Cap off your talk by putting the word remember before your proverb

Give PSP a try and let me know how it worked out.

by Ron Ploof | Oct 29, 2018 | Business Storytelling

One of my movie-watching pet peeves is non-musician actors playing instruments. My issue usually manifests itself as a mismatch between the video and soundtrack. For example, as a percussionist, I’m highly sensitive to non-musician drummers waving their arms without hitting anything, or even worse, striking cymbals, snare drums or tom-toms out of sync with the soundtrack. And don’t even get me started about non-musician guitar players. There is nothing more frustrating than watching an actor strumming clumsily while sliding his lifeless hand along the guitar’s neck without any attempt at playing a chord. Such distractions negatively impact my willingness to suspend belief.

All storytellers must fix story problems. In the case of the non-musician actor, visual storytellers must find a movie-magic way to cover up the fact that the actor can’t play. One technique is to hide the musician’s hands, either by using an obstructed camera angle (behind the piano), or a tight shot on the hands of a “stunt musician.” Both techniques, however, tend to draw my attention to the problem as I want to see a full-frame shot of the character playing.

I’ve always wondered, why can’t they just teach the actor how to play something—ANYTHING—to augment the various cuts with at least one full-frame shot? Anyone can learn to play a few guitar chords or play a simple drum beat for a few seconds.

Non-musician actors aren’t the only distractions that pull me out of a story. Consider these other distracting storyteller fixes:

1. The antagonist needs a mysterious device that can be used to destroy the world. What’s the easiest way to go? Use a “microchip.”

2. A crime fighter reviews video footage of a getaway car. The storyteller chooses between two uninspired ways to extract information from the video: a) zoom in to read a perfectly clear version of the license plate (which is impossible from a picture-resolution perspective) or b) have the character acknowledge the zooming-in problem, but can “clean it up” through magical image processing software…or a microchip!

3. And my all-time favorite…the cops are stumped for clues, so, they approach some clairvoyant petty thief. “Word on the street,” the informant says, “is that Mr. Big is gonna hit the bank tonight at midnight.” Really? Mr. Big shares such information with the guy selling stolen watches on the corner?

Storytellers have an obligation to hold their readers attention, thus must solve their problems in a believable way. Ask yourself, does my story have too much detail, too few characters, or too many plot twists? Are the solutions to my story problems realistic or do they cause distractions? Tackling these issues now will save much grief in the future.

Photo Credit: Mayer, Frank Blackwell. The Continentals / FBM. , 1875. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2006680120/.

by Ron Ploof | Oct 15, 2018 | Business Storytelling

Susan Carnicero is a former CIA agent who specializes in spotting deception. I first learned of her through a YouTube video of her teaching how to tell if someone is lying. One of the deception techniques jumped out at me. People who lie convince while those telling the truth convey.

The distinction resonated with me. I once had an old boss who always said, “We need to manage the customer’s expectations.” I’ve always hated that statement and now understood why. He wanted us to convince while I like to convey.

Susan explains that “…a convincing statement is the strongest arrow…” in a liar’s quiver, because “we all want to be convinced. We want to believe that all people are good and that they’re always telling us the truth.”

For example, there are only two appropriate answers to the question, “Did you steal the merchandise?” Yes or no. However, a liar might say something like, “I’ve been loyal to this company for so long; I’ve never given you any reason to think that I’m a thief; or how could you ask me something like that?” Notice that none of these responses contain a denial. The person is trying to convince not convey.

My former boss sees marketing’s role as one to convince as opposed to convey. Convincing copy is easily identifiable through an abundance of hyphenated terms like: world-class, state-of-the-art, easy-to-use, thought-leader, industry-leading, leading-edge, etc… All are designed to convince not convey.

Susan leaves us with one last thing to consider when folks lay it on too thickly by invoking God’s name, swearing on a relative’s grave, or using hyphenated marketing terms. “Convincing statements sound so true, or in this case, irrefutable.” But they still don’t answer the question.

The next time your write some marketing copy, ask yourself the following question. Am I trying to convince or convey? If it’s the former, try rewriting for the latter.

Photo Credit: Jim Thompson under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-SA 2.0)