In the late 1950s, Stan Freberg questioned the status quo. He despised hard sell advertising and imagined spots driven by honesty and humor instead. And so he formed Freberg Ltd (but not very), an agency with the motto: “More honesty than the client had in mind.” Known to many as the father of the funny commercial, Freberg was an advertising innovator.

Successful innovation, though, needs more than just an innovator. Without the ability to explain a new idea, application, or concept, innovative ideas die on the vine. Getting others excited about the idea requires someone who can link concepts to meaning and meanings to audience understanding.

Innovators and storytellers are kindred spirits. Both create something from nothing. Both look at the same thing as “normal people” yet refuse to accept the obvious assessment. If given a choice between two things, storytellers and innovators frequently seek the third alternative…or the fourth…or the fifth.

Stan Freberg was both an innovator and a storyteller who helped his clients to look beyond the obvious.

For example, in 1959, Kaiser Aluminum Foil had a problem. Local grocers had allocated most of their shelf space to Reynolds and Alcoa, leaving Kaiser with a paltry five percent market share. Kaiser’s agency of record, Young & Rubicam, approached Freberg for innovative ideas on changing the situation.

He pitched a series of radio and television ads about a downtrodden Kaiser Aluminum Foil sales rep named Clark who pleaded with grocers for shelf space. He described the financial burdens that the shelf-space problem placed on Clark’s family. In one sketch, when his daughter asked why she couldn’t have new shoes, Clark tells her, “…because the mean old grocers won’t stock Daddy’s foil.”

Y&R listed many concerns with Freberg’s unorthodox approach. First, the campaign revealed a weakness–something that no company wants to admit. Second, they worried about the potential backlash of offended grocers. Lastly, they pointed out that the campaign violated a fundamental business principle of the Harvard Business School: advertising cannot force distribution.

Freberg’s ignorance of the HBS rule actually gave him the freedom to slay a sacred cow. Fifty years before social media, Freberg understood something that the 1959 Harvard Business School didn’t–the power of the consumers–who came out in droves to demand shelf space for Kaiser Aluminum Foil.

Did advertising end up driving distribution? By the time the campaign ended, Kaiser Aluminum Foil had added 43,000 new outlets for its product.

Innovation and storytellers go hand in hand.

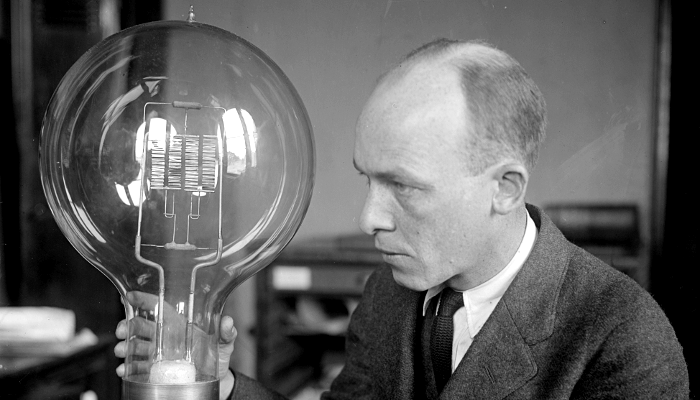

Photo Credit: Library of Congress

To read more about Stan Freberg and The Kaiser Aluminum Foil story, read Chapter 17: You Could Have Foiled Me in his autobiography, It Only Hurts When I Laugh. ISBN: 0812912977