Information is Beautiful recently published an article, Based on a True Story, that fact-checked movie scenes and depicted the results graphically.

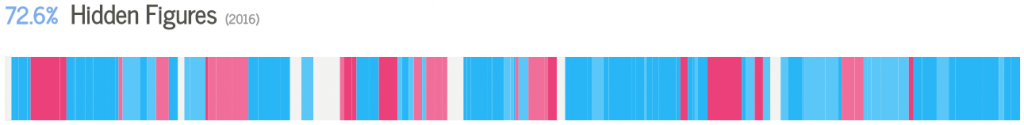

Here’s an example from the movie, Hidden Figures:

Each bar represents a scene and its “truthfulness.”

When I first saw this data, the 76.2% trueness rating felt slimy. I love this movie and want to believe that EVERYTHING in it was true. But, taking a step back, does it really matter?

Telling a story based on actual events is tricky because life is a jumbled mess of imperfect humans reacting to random situations. The human condition is hard enough to understand from an individual’s perspective let alone trying to explain it to someone else. And while audiences fully accept the premise that life is messy, they prefer their stories to be organized, and so they grant storytellers some leeway with facts.

We touched upon this concept almost two years ago with the post, Be a Storyteller, not a Liar.

“A storyteller makes up things to help other people; a liar makes up things to help himself.”

― Daniel Wallace

Storytellers have an ethical responsibility to help their audiences through entertainment, education, wisdom, etc.. Simultaneously, they must counterbalance that obligation by making stories interesting. And therein lies the ethical rub. Where do they draw the lines? How do storytellers choose which facts to use, omit, or modify while maintaining the story’s integrity?

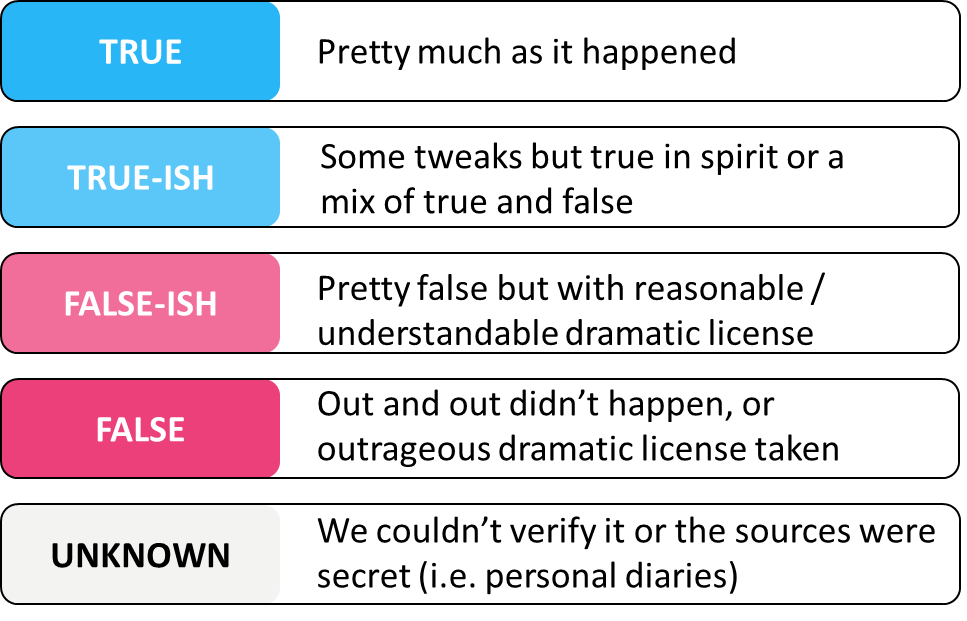

Let me introduce a tool called DOTS — an acronym that stands for Details, Order, Time, and Substitution.

Some details are more important than others. Therefore, storytellers must choose which details advance the story while eliminating all others. (See Take the Air Out of Bloated Content with Chekhov’s Gun). For example, one scene from Hidden Figures demonstrates the inhumanity of racism when Katherine is forced to use a separate coffee pot than her white co-workers. The coffee pot is important. It’s particular brand, model, and metallic finish, however, isn’t.

Stories don’t have to be told in the order by which they occurred. Life events, ABC, can be told as BAC, CAB, ACB, BCA, or CBA as long as the reshuffling helps the listener and doesn’t change the meaning. Hidden Figures uses flashbacks of Katherine learning math as a young girl to boost the meaning of present scenes.

Editing for time is the easiest of the storytelling edits to understand. While the Hidden Figures story spans several years, its storytellers obviously compressed time by using only 127 minutes to tell it.

Audiences accept, even encourage storytellers to play with time, whether it be through compression or expansion. Expansion is used when an event takes more time to describe than it took to play out. For example, have you ever had a moment where time stood still while you processed volumes of information in an instant? Malcolm Gladwell uses this technique often in his bestseller, Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking, where he dedicates several pages to describe a thought processes that only last for fractions of a second.

Sometimes precise facts hinder a story, requiring the storyteller to alter them. For example, what if Katherine arrived at a revolutionary concept after conversations with dozens of people? If the idea helps advance the story, does it really matter how she arrived at the idea? To save time, what if the storyteller combined all of Katherine’s conversations with a single one? As long as the substitution doesn’t change the meaning, the substitution passes the ethical tests.

DOTS is a tool that helps find the balance point without crossing ethical lines. The next time you need to tell a story based on true events, give it a spin.

Photo Credit: Fisher, Alan, photographer. [Grange & Zeller tackle / World Telegram & Sun photo by Alan Fisher]. Chicago Illinois, 1935. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2013646412/.