by Ron Ploof | Jul 25, 2016 | Business Storytelling

Storytelling lessons can come from the most unlikely places. I learned one of mine while attending my first National Football League game as a fourteen-year-old boy.

I remember the game as if it were yesterday. The Seattle Seahawks played the New England Patriots in the pouring rain. So much water had pooled on the astroturf that the groundskeepers used snowplows on pickup trucks as massive squeegees. I remember standing there at the end of the game, soaking wet, but rather than feeling miserable, I felt joy. The final score didn’t hurt, either. The Patriots won, 31-0.

My storytelling lesson came when Dad explained how he watched football games differently in a stadium.

“Television makes you watch what the camera is pointed at,” Dad said. “The action follows the football in the hands of skilled players like the quarterback, running back, or receivers.”

He handed me his binoculars and pointed to the line of scrimmage. “On this play, watch the linemen instead of the ball.”

The powerful lenses transported me into the middle of an amazing scene where 300-pound men collided with other 300-pound men, pitting strength against strength and will against will.

“Games are won and lost in the trenches,” Dad said. “Without their blocking and tackling, the skilled players can’t do their jobs.”

Beginner storytellers tend to craft their stories like television broadcasts, focusing on major characters as opposed to minor characters. And while a story’s excitement follows the major characters, master storytellers understand that the backbone of that excitement is set by those who battle in the trenches.

Minor characters make the story possible. They enhance major character’s traits. For example:

- While we all loved listening to a charismatic Steve Jobs, he never would have become the leader of Apple without the support of the quiet and geeky Steve Wozniak.

- Just as the game of football needs a field to play on, stories need settings (StoryHow PitchDeck #12). For example, the Cold War played an important role in NASA’s attempt to put an astronaut on the moon.

- And just as a football game would be silly without a football, stories need props, like sacred cows (StoryHow PitchDeck #15), catalysts (StoryHow PitchDeck Card # 9) or pawns (StoryHow PitchDeck Card #10) to make the story that much more impactful.

Without minor characters, stories fall flat and their messages lack punch. If you want your audience to empathize with your customer hero, place her in danger by revealing a fatal flaw (SHPD Card # 11). If you want listeners to hate your antagonist, have him kick a puppy.

But be careful. Minor characters can also become distractions. While exchanging the binoculars with my Dad, my teenage brain found a particular group of minor characters infinitely more interesting than the linemen. I think they were called cheerleaders.

Photo: Library of Congress

by Ron Ploof | Jul 18, 2016 | Business Storytelling

Marketers look for ways to differentiate their products from the rest. When representing a product with an unmatched capability, the job is easy. But, more often than not, marketers represent products that are similar to a competitor’s offering. Business storytelling is applicable at moments like these because the stories associated with a product are unique and unique stories have value.

Consider a baseball. All Major League baseballs are manufactured to the same specifications.

- All weigh between 5 and 5.25 ounces

- All have a circumference between 9 and 9.25 inches

- All are wrapped with two strips of rawhide that are held together by 108 double stitches.

Essentially, baseballs are a commodity that we can buy online for $19.99.

But, if each baseball is indistinguishable from any other, why would someone pay significantly more than $19.99 for one? The answers depend on the stories attached to them.

For example, someone paid $3 million for Mark McGwire’s 70th homerun ball. Someone else paid $418,250 for the ball that dribbled between Bill Buckner’s legs, allowing the New York Mets to advance to Game Seven and beat the Boston Red Sox in the 1986 World Series.

In Rhetoric, Aristotle describes the three components of persuasion: ethos (credibility), logos (facts), and pathos (emotion). All three are required to persuade. In the case of Bill Buckner’s baseball, all three were required to persuade someone to open their checkbook:

- Logos (Fact): The baseball for sale dribbled between Bill Buckner’s legs

- Ethos (Credibility): An MLB official verified that the ball in question was that same as the one that bounced into right field.

Logos and ethos are factual but don’t affect the perceived value of the baseball. Pathos drives the price.

- Pathos (Emotion): A die hard NY Mets fan wanted that baseball and was willing to pay for it.

Note that the baseball’s value is tied to the wants of a very specific buyer. To the Mets fan, the baseball is a conversation piece that represents a feeling of triumph and elation. But, to someone like me who grew up as a Boston Red Sox Fan, I never wanna see that ball again. I can only hope that someday in the future, it’s found by a kid who takes it outside and loses it in the sewer.

Stories have value. No story; no additional value beyond the commoditized price. Our job as business storytellers is to make that connection.

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baseball_(ball)

by Ron Ploof | Jul 11, 2016 | Business Storytelling

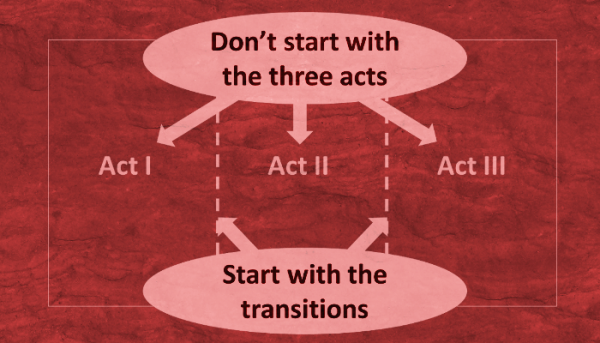

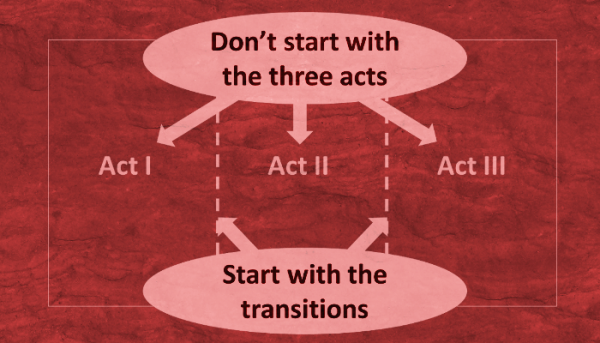

Over the past couple of years, I’ve noticed how many new business storytellers experience writer’s block while trying to use the three-act story structure. Their problem isn’t with the structure, per se, but rather their struggle to figure out what goes into each act. The good news is that I have a technique for getting over this issue.

First, let’s define each act:

- Act I establishes the steady-state situation before a change is introduced.

- Act II contains the situational ripples that result from the change.

- Act III contains the new steady-state after the change is addressed.

The key to unlocking three-act writer’s block is found in the common word within each definition. Since all three acts involve change, I recommend focusing on it as opposed to the acts themselves by asking two questions:

- What changed to transform a stable situation into an unstable one?

- What did the people do to establish a new stable situation?

The answer to question #1 describes the transition from Act I to Act II. The answer to question #2 describes the transition from Act II to Act III. By asking questions about the transitions instead of the acts themselves, it’s easier to generate a content list for the things that must go into each act.

For example:

Question #1: What changed to transform a stable situation into an unstable one?

ACME manufactures widgets by hand. Until recently, the company has always been able to keep up with demand. However, when a celebrity tweeted some love about ACME’s flagship product, orders spiked, outstripping ACME’s manufacturing capacity, increasing backlog, delaying shipments, and as a result, impatient customers began canceling their orders.

Question #2: What did people do to establish a new stable situation?

ACME sought, found, and installed a widget machine that increased its manufacturing capacity.

By defining the transitions between the acts, we can now fill in the details around them.

- Act 1: contains why ACME Widget needed a better way to manufacture widgets

- Act 2: contains the process that the company used to find this better way.

- Act 3: contains how the machine has changed the way ACME does business.

The next time you are trying to write a business story by using the three-act structure, focus on the transitions and the acts will take care of themselves.

by Ron Ploof | Jul 5, 2016 | Business Storytelling

“So, I’m standing behind this odd little man at Starbucks,” your friend says.

“Yeah?” you ask, anticipating a good story.

“He goes to the counter and orders a ‘Cup-o-Joe, for Joe, to go,’” she says, complete with air quotes. “Isn’t that funny?”

“Yeah,” you fib.

She continues. “Then, I trip while walking to my car.”

“Oh, no! Did you get hurt?” you ask.

“No,” she says. “But I almost spilled my coffee. Then, I get into my car and notice that I’m almost out of gas.”

We’ve all been in situations like this before. We’re listening to a friend tell a story, but our attention wanes and we wonder, Where is this story going? Why is she telling me this? Will all of these facts (odd little man, tripping in the parking lot, and running out of gas) come together somehow?

“Luckily,” she continues, “I got to the gas station just as the warning light came on.”

And there it is. The answer is no.

So what’s happening? Why is this story an epic fail? Why do you feel like gouging your eye with a rusty fork?

It’s because you aren’t listening to a story. It’s a narrative. And while many people use the words interchangeably, they are different.

A narrative is a collection of facts, like odd little men, coffee spills, or almost running out of gas. A story is the result of people pursuing what they want, followed by the difficulties experienced during their quest. Bestselling author, Robert McKee explains, “All stories are narratives. But, not all narratives are stories.”

Your friend’s narrative could have become a story had it contained some different things. For example:

- if the odd little man had forgotten his wallet and she paid for his coffee.

- if she spilled her coffee on her expensive new shoes while on the way to an important client who always compliments her shoes.

- if she combined all three facts, such as running out of gas and then being helped by the odd little man who pulled up in his shoe-shine truck.

Most marketers are great at telling narratives because they’re experts in stringing together facts, feeds, speeds, features, and benefits. Rarely are these narratives considered stories, however, because those facts are never put into the context of people pursuing what they want.

The next time you write a piece of marketing material, ask yourself, “Is this a narrative or a story?”

by Ron Ploof | Jun 27, 2016 | Business Storytelling

Writers typically think of Point of View (POV) as the person who’s telling the story. Storytellers, however, add a level of sophistication by considering the multiple POVs that exist within it. Since each role (customer, vendor, investor, employee, etc.) reacts differently to events depending on what they know, savvy business storytellers structure their stories around Who Knows What? (StoryHow™ PitchDeck Card #42).

For example, let’s look at the story-structure possibilities surrounding a hungry man about to bite into an apple with a worm in it. A storyteller can influence an audience’s perception by choosing Who Knows What?.

1. The audience knows more than the man:

If the audience knows about the worm but the man doesn’t, the storyteller has two options:

a. If members of the audience care about the man, they will empathize with him, experiencing emotions of stress and discomfort as he’s biting into the apple.

b. If the man is unlikeable, comedy may ensue as the audience delights in his comeuppance.

2. The man knows more than the audience.

If a storyteller gives a character more information than the audience, she must also fill that void by leaving clues, such as describing the man’s strange behavior. In this case, the audience will wonder why the man is behaving oddly until the storyteller chooses to reveal one of two things: the hole in the apple or what’s left of the worm.

3. The man and the audience know the same thing.

Another way storytellers steer an audience is to give each the same knowledge. Here are three situational possibilities:

a. They both know that there’s a worm in the apple. Perhaps the man has been challenged to a dare. In this case, the audience and the man share feelings such as anticipation, stress, and disgust.

b. Neither knows that there’s a worm in the apple. If neither the audience nor the character knows that the apple contains a worm, there’s no suspense leading up to the bite, but both will share in the horror of the afterbite.

c. Neither knows about the worm, but another character does. Perhaps a prankster has given the man an apple with a worm in it. While neither the man nor the audience knows about the worm, the storyteller ensures that one or both notice the prankster’s strange behavior. While the prankster’s actions are seen as perplexing pre-bite, both the audience and the man will understand everything post-bite.

We’ve shown six different ways of using Who Knows What? with just three roles: man, audience, and a prankster. A storyteller’s opportunity to change the audience’s perception increases exponentially by adding more POVs–such as the worm’s.

4. Look at the story from the worm’s POV:

a. If the worm doesn’t know about the man, the story is a tragedy.

b. If the worm knows about the man, the storyteller can write a suspense-thriller or a comedy.

It all depends on Who Knows What?

So, how can you use the concept of Who Knows What? to change the way an audience participates with your story?

by Ron Ploof | Jun 20, 2016 | Business Storytelling

Most business presentations fail because they’re stuffed with too much information. Rather than selecting the most relevant facts, presenters force their audiences to sift through a mound of data to find the golden nuggets contained within.

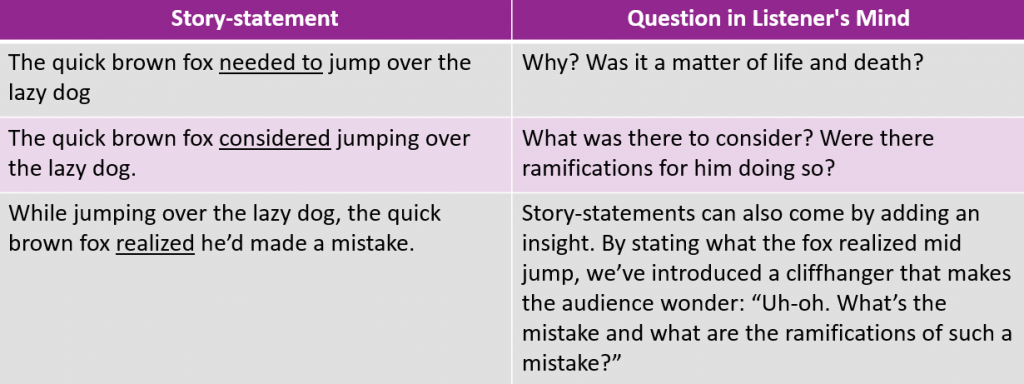

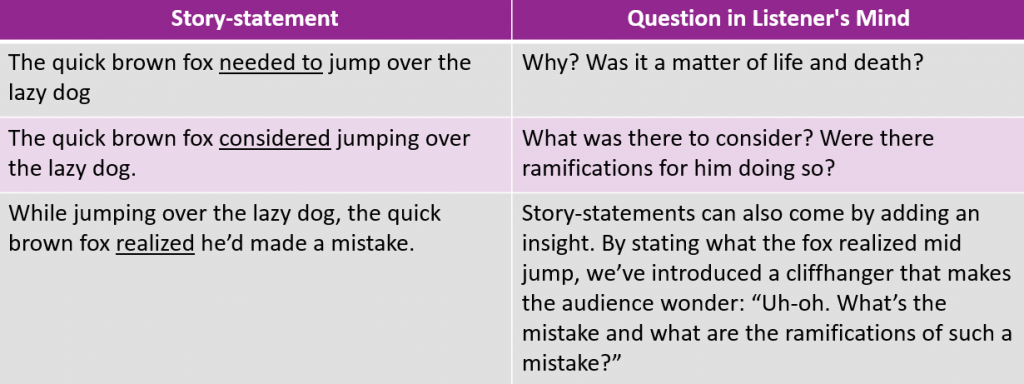

Business storytellers do something different. Rather than forcing a listener to pan for the gold, storytellers place whole nuggets into their pans, leaving them to ponder how the chunks got there. In other words, storytellers don’t just state facts, they make story statements.

Let’s take a look at the difference using the following famous sentence:

The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog.

The sentence contains a simple fact. It’s like saying the sky is blue, the product is rated number one, or the company hit its quarterly goal. There’s nothing that a listener can do with this information other than to just accept it passively. However, by making a slight modification, we can transform this factoid into a story statement.

The quick brown fox wanted to jump over the lazy dog.

Story statements do two things: deliver a fact while simultaneously spawning a question within a listener’s mind. When listeners hear a story statement, their Neural Story Nets compel them to wonder what comes next.

- Why did he want to jump over the dog?”

- “Did he make it?”

- “Is there something that’s keeping him from doing so?”

By stating what the fox wants instead of what the fox did, storytellers transform an audience from passive listeners into active participants.

Here are some story statement alternatives:

In each of these cases, we’ve modified the facts in such a way that compels the audience to want to know more.

Think about your next business presentation. List the most important facts that you must convey. Now, rather than spewing them rapid-fire, turn them into story statements. If you deliver them correctly, your audience will feel as an integral part of your presentation rather than a passive target to dump data upon.

Photo Credit: Library of Congress