Ron on The Duct Tape Marketing Podcast

Ron was interviewed recently on the Duct Tape Marketing Podcast with John Jantsch. Take a listen.

Ron was interviewed recently on the Duct Tape Marketing Podcast with John Jantsch. Take a listen.

All stories are mysteries. Some are just bigger than others. The best stories present listeners with a series of facts that leave open questions, resulting in listeners wanting to hear more. When done well, one final missing piece of information pulls the entire story together, adding final context and meaning.

![]()

I walked the length of Terminal B at Mineta San Jose International Airport in search of the shortest line. There was only one person waiting to dine at San Jose Joe’s–a woman, probably in her early thirties. About five minutes later, the waitress seated her, leaving me on deck. I looked for any signs that a table might be opening soon, but it didn’t look good.

That’s when the waitress said, “The woman that I just seated says that she doesn’t mind if you sit at her table.”

Folks, let’s be real here. I’m a middle-aged man. If a young woman offers to share her table with me, I’m going to agree without hesitation.

I weaved my way through the tightly packed tables and sat down. “Thank you so much for letting me sit here,” I said.

She looked up from her phone. “Of course,” she said, gesturing to the table for four. “It’s a waste for one person to be taking up this large table.”

I noticed it instantly. There was something unique about her–the way she answered, the calmness of her demeanor, let alone the fact that she was comfortable sharing a table with a perfect stranger. She exuded a self-confidence. Not one of false bravado or arrogance, but a real, comfortable-in-one’s-own-skin type of strength that’s rarely seen. There had to be a story behind this behavior and the storyteller in me needed to know what it was.

“Where are you from?” I asked.

She placed her cell phone face down on the table. Usually, when people do this, it’s with a sense of annoyance, but not my impromptu dinner partner. She did so with the intention of being fully present.

“South Carolina,” she said. She worked for Google as a sustainability manager and was on her way home after a long business trip.

She then asked me the same question. It was clear that she wasn’t just being polite. She truly wanted to know. This young woman exhibited something that I’ve struggled with for my entire life–the ability to ignore distractions and live in the moment.

We continued our discussion over dinner. I learned that both she and her husband travel for work and that they hadn’t seen each other in almost a month. And although it would have made logical sense for her to stay in San Jose this weekend, she wanted to spend a few days with him before she trekked back to the Bay Area next week.

I hadn’t yet found the story yet, but I had gathered enough information to identify her special trait as something I’d seen before, yet in a different context. I glanced at my watch to see that time was running out. I had to solve this mystery before we went our separate ways forever.

“So, what did you do before joining Google?” I asked.

“I was a Nuclear Electricians Mate in the Navy.”

That was it! She was a sailor. The special trait that she’d been exhibiting was similar to one that I’ve observed in working with three generations of sailors during my volunteer work for Battleship IOWA. No wonder she felt so comfortable sharing her table with a perfect stranger. She felt at home in cramped places with hundreds or depending upon the ship, thousands of shipmates.

I smiled, pleased that I had solved the mystery before dinner was over. “Thank you for your service,” I said.

For the first time that evening, she revealed a little self-consciousness. “You’re welcome.”

“So, you’re a sailor,” I said. “I should have known. I’ve been around enough of them.” I then described my work with the IOWA and the men who served aboard her.

Soon it was time to head off toward our respective flights. She got up to head to her gate.

“By the way,” I said, “What’s your name?”

“Sara,” she said.

“Nice to meet you, Sara. I’m Ron.”

“It’s been a pleasure, Ron. Have a safe flight.”

And that was it. Sara headed to catch her flight to South Carolina while I headed to catch mine to Orange County.

From the moment I met her, I knew that she had a story. Something in our interaction sounded familiar, but I couldn’t put my finger on it. The clues were there, but I couldn’t piece them together.

Think about your favorite customers. Is there something about the way they act, the things that they say, or the way they say them? Do they have a familiar accent, an interesting tattoo, or always take their lunch at 12:12?

Take the time to notice. Then invest the time to uncover the story behind your observations.

In other words, have dinner with a sailor.

Photo Credit: Jacksonville, Florida. Fighting French sailors messing at the United States Naval air station. Duval County Florida Jacksonville, 1942. Oct. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/owi2001045644/PP/

The SUV had been bouncing on the dirt road for at least an hour when the driver made a sudden stop. Matt looked up from his video equipment to see that a truck had stopped a few yards ahead, thus impeding his vehicle’s progress. It wasn’t the first time that he had seen something like this. The news cameraman had witnessed dozens of broken down vehicles during his assignment in war-torn Nicaragua. But something about this particular instance felt different.

The driver pleaded with both Matt and the reporter to stay in the SUV, but they got out to investigate anyways. That’s when the two understood the source of the driver’s anxiety. A military roadblock appeared about twenty yards ahead of the stopped truck. Matt’s American news team had stumbled into a standoff between government soldiers and rebels.

Instinctively, Matt stepped away from the SUV to get a better view and pointed his video camera toward the commotion. He zoomed-in to see a puff of smoke emerge from one of the roadblock guard’s rifles, followed immediately by the sound of it firing. The rebels countered with their own volley, escalating the standoff into an all-hands shootout.

Matt had placed himself in the perfect position to film the skirmish. By standing behind the rebels, his camera could capture both sides of the conflict. However, while this position proved perfect from a photographic perspective, it posed a safety issue. Standing behind a target increased one’s chances of becoming a casualty of war.

“Weren’t you scared?” I asked.

“I should have been,” Matt said. “I could hear stray bullets whizzing by my head. But no. I wasn’t.”

“Why?” I asked.

“Because you can’t get hurt watching television.”

Matt explained that in the moment, he didn’t see himself as a cameraman in the middle of a shootout. Instead, he was an observer watching a movie scene play out in his viewfinder.

The stories that we tell ourselves are powerful. They can make us walk through fire or run from it. They can make safe situations feel dangerous, or give us a false sense of security as real bullets fly by our heads. We are motivated by the stories that we tell ourselves.

So, which stories are you telling yourself? Which ones are your customers telling themselves?

Photo Credit: Harris & Ewing, photographer. [Man and Woman With Rifle?]. United States, 1924. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/hec2013014721/.

Last post, we described Princeton’s experiment that showed how stories facilitate brain-synchronization between listeners and storytellers. This week, we’ll look at the University’s research into the relationship between stories and the human memory.

The experiment:

The experiment resulted in three conclusions. The first two duplicated what we learned with mirror neurons. The third conclusion, however, was significant.

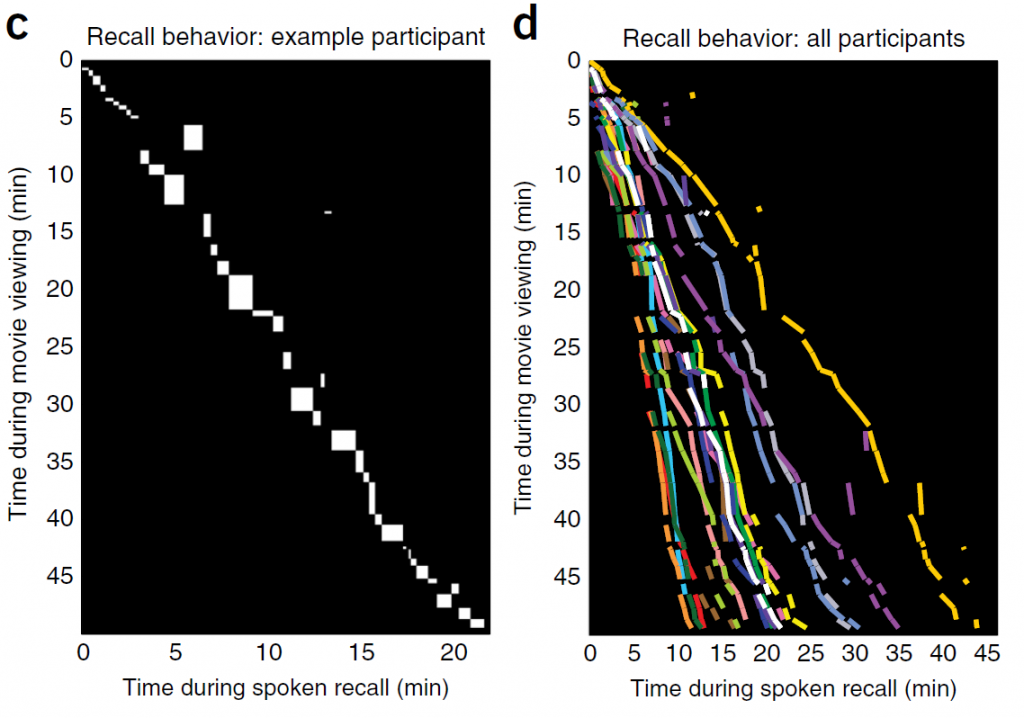

The researchers compared two types of recall: movie-to-recall and recall-to-recall. Movie-to-recall compares what a participant recalled to the actual movie details. Recall-to-recall compares the details of what each participant recalled.

“Strikingly…we found that recall-recall similarity (the details each participant recalled compared with the other recollections) was stronger than movie-recall similarity (the details each participant recalled compared to the actual movie), indicating that the neural representations were transformed between perception and recall in a systematic manner across individuals.”1

In other words, although the movie watchers recalled different things, the ones that they did remember were common. This result is counterintuitive, considering that we filter our perceptions through different experiences and vocabularies.

“A memory is not a perfect replica of the original experience; perceptually representations undergo modifications in the brain before reflection that may increase the usefulness of memory, for example, by emphasizing certain aspects of the precept and discarding others.”2

Therefore, if our memories are imperfect, shouldn’t we expect the imperfections to be random instead of common? The report thinks so.

“If recall patterns were merely a noisy version of the movie events, we would expect the opposite result: lower recall–recall similarity than movie–recall similarity. No regions in the brain showed this opposite pattern. Thus, the analysis revealed alterations of neural representations between movie viewing and recall that were systematic (shared) across subjects.”3

We alter our perceptions based on unique perspectives, worldview, and life experience. However, this experiment revealed that even though we each encode our memories differently, we tend to remember the same things. But why?

A clue is found in the data. The researchers divided the Sherlock episode into fifty scenes. By tallying the data and comparing what people remembered from each scene, a pattern emerged.

Figure C shows how one participant recalled the episode. Note that since the episode lasted 50 minutes (Y-axis) and the participant took over 20 minutes to recall it (X-axis), that some details were lost. Figure D illustrates how all 17 participants recalled the movie. Also, note the wide range of recall times. It took between 10 and 45 minutes to recall the details of the episode. 4

However, although the recall-to-movie details differed—the researchers found that collectively, the group recalled similar elements. This is even more amazing considering that the none of the participants were prompted for their recitations.

So, how did these participants remember the same parts of the story? I propose that the StoryHow PitchDeck™ has the answer.

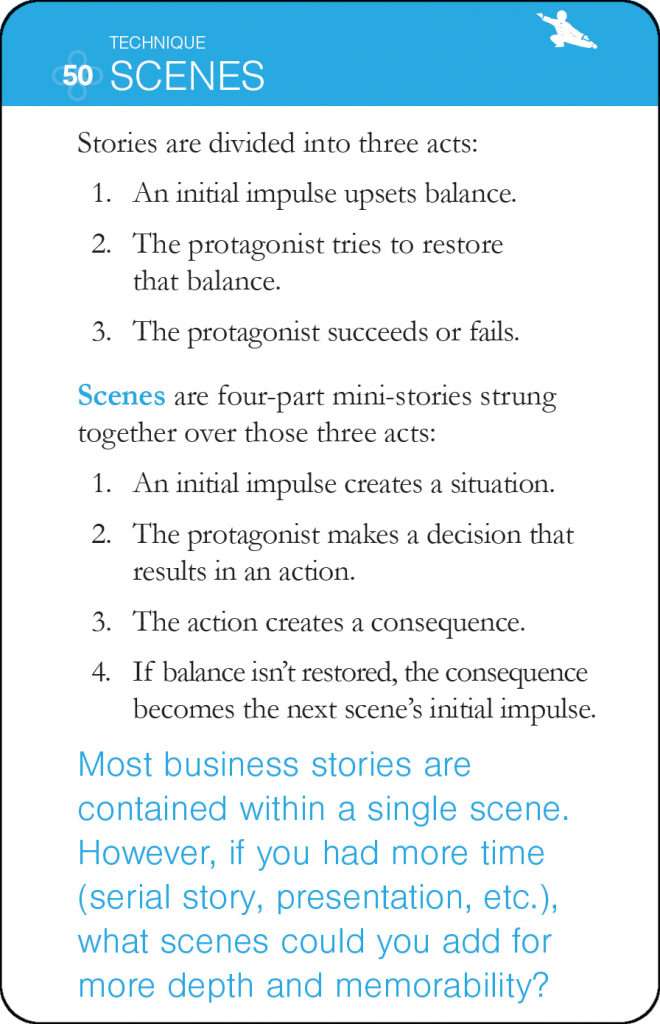

According to StoryHow PitchDeck Card #50: Scenes are mini-stories.

If the consequence doesn’t resolve the problem, it then becomes the initial impulse (then one day) for a subsequent scene. Thus, if a participant wants to remember the Sherlock episode, all they need to do is follow the breadcrumbs of “then one days” and “consequences.”

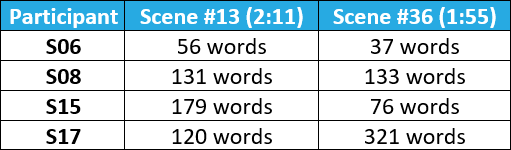

Supplementary data from the study5 backs up this “Scene Theory.” Consider the following table that summarizes the number of words that four participants used to describe two scenes #13 & #36.

Although the number of details that each participant recalled varied (participant S06 used 37 words to describe Scene #36 compared with participant S17 who used 321), all four participants got the salient points:

By comparing the common things that each participant recalled, a pattern emerges. Each scene has some sort of mystery (like a rash of suicides or ringing telephone booths) followed by an action (Sherlock’s invitation and Watson getting into a strange car). Since these actions didn’t resolve anything, they become the impetus for subsequent scenes.

By segmenting their data by scene, the researchers found the connection between story and memory. People don’t remember every detail of a story. Instead, we remember the things that have meaning to us. Since we each have different interests, the specific things that we remember differ, as demonstrated by the fact that participant S17 remembered almost 10 times more details of a scene than S06. But, in the end, they both remembered the most important parts of the scene–how it connected to the rest of the story.

These two studies prove something that we’ve always known intuitively: people connect through stories and our memories depend upon them.

Notes:

Photo Credit: Genthe, Arnold, photographer. Arnold Genthe seated outdoors with two friends. , None. Between 1911 and 1942. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/agc1996016301/PP/

Have you ever met someone and felt an instant connection, where you found yourself finishing their sentences while they did the same with yours? Well, that feeling of connectedness has a scientific name. It’s called neural coupling.

Neural coupling occurs when two people’s brains synchronize. It’s a neurological phenomenon where complementary brain regions activate simultaneously and the folks over at the Princeton Neuroscience Institute (PNI) have video evidence of it happening.

In 2010, Princeton researchers Greg J. Stephens, Lauren J. Silbert, and Uri Hasson released a paper called, Speaker-listener Neural Coupling Underlies Successful Communications, which describes their experimentation with stories and neural coupling.

The experiment consisted of two parts. First, a Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) machine monitored the brain activity of someone telling a personal story. Next, the team monitored someone else’s brain activity while they listened to a recording of that story. When the fMRI results were placed side-by-side, the researchers captured images of the listener’s brain actively mimicking that of the speaker’s brain.

But that’s not the most exciting part of the research.

Most of the time, the listener’s mirror neurons lit up a fraction of a second AFTER those in the speaker’s brain, which makes sense intuitively. For example, if you tell me a story, little delays accumulate as you form the words, those words travel through the air to my ears and my brain processes that sound into language until finally activating my mirror neurons. But that’s when the researchers noticed something not-so-intuitive. At certain times during the story, the listener’s mirror neurons fired BEFORE those in the speaker’s brain. Put another way, they activated BEFORE the speaker articulated the next part of the story.

How freaky is that? Did the Princeton researchers find evidence of some kind of Vulcan Mind Meld? Sort of. The report describes these precognitive events as “anticipatory responses,” where the listener’s brain attempts to predict the next part of the story.

If you’ve been reading this blog for a while, you already know why these events happen: Kenn Adams’ Story Spine:

Once upon a time

Every day…

Then one day…

And because of that…

And because of that…

Until finally…

And ever since then…

Since we’re accustomed to stories following the Story Spine, we’re always assessing story situations and anticipating what happens next. Therefore, when we hear a Once upon a time, we know that a Then one day is probably not far behind. Then one days have repercussions that lead to and because of that, and because of that, until finally.

Creatives frequently describe the power of stories using terms like metaphysical, spiritual, or ethereal. Analytics dismiss such definitions as soft or non-scientific. Yet, this research clearly presents hard facts that two human brains can sync up in predictable ways.

Next post we’ll cover the PNI’s most recent research that demonstrates the relationship between stories and the human memory. Stay tuned.

Photo Credit: Genthe, Arnold, photographer. Arnold Genthe seated outdoors with two friends. , None. Between 1911 and 1942. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/agc1996016301/PP/

Storytelling is hard because it requires observation time. Most people are in such a rush, running from appointment to appointment, that they have little opportunity to develop their craft as storytellers.

Recently, I’ve been flying on Southwest Airlines—you know, the airline without assigned seating. I like to watch the road warriors in their single-minded quests to secure forward-cabin aisle seats for the sole purpose of deplaning quickly. Road warriors are story-handicapped because they’re always planning their next move and thus can never live in the moment.

I prefer the window seat, where I press my nose against the glass and watch everything–the flaps extending, the taxiing, and counting the number of planes ahead of us for takeoff. My favorite part of the flight is when the pilot throttles up the engines while standing on the brakes. The moment is one of anticipation, a prelude to a battle between human power and nature’s power. The plane then lurches forward, pressing its passengers into their seats as thrust and lift conspire to defy gravity and carry them to the clouds.

I’ve seen the most beautiful sunsets through airplane windows. My favorite occurred once as the sun cast burnt-orange rays upon the clouds below us. I hoped in vain to stop time, realizing that the gorgeous view would end as soon as we broke through the puffy carpet of orange and purple. But that’s when something unexpected happened. As we broke through the first carpet, we found a second one below. The sun’s rays, now channeled between two cloud layers, reflected their orange and purple hues both above and below us. A few of my fellow window-dwellers gasped at the site. Most of the road warriors toiled in oblivion.

I love final descents because that’s when I get to observe the world at three different scales. The macro level reveals the topography, where hills become valleys that create rivers that fill lakes. The middle level shows civilization, where human-made structures like roads, buildings, power lines, and sports fields emerge from the topography. And finally, if I’m lucky enough, I’ll catch a glimpse of the micro level to see the people who live in those houses, work in those buildings, or play in those fields.

Storytellers live in the moment. They observe life and reflect upon what they experience. And they do so by sitting in the window seat.

Photo Credit: Palmer, Alfred T, photographer. California Long Beach, 1942. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/fsa1992001582/PP/.