by Ron Ploof | Aug 14, 2017 | Business Storytelling

One of the reasons why marketers make terrible storytellers is because they’re compelled to tell us EVERYTHING about their product or service. Longtime StoryHow readers, however, understand that’s not how stories work. The best way to hold people’s attention is to give them less information, not more.

The best storytellers assign their audiences some work. Rather than spoon-feeding every detail, they dole out information drip-by-drip, making audiences feel off balance while they try to stitch those bits into some coherent meaning. And there’s one more thing that the great storytellers understand. People tend to connect partial dots negatively. Why? Because worst case scenarios make the best stories.

My Nissan Maxima is easy to identify by its personalized license plate. One day, my friend Terrence saw my car and noticed a young woman in the passenger seat. He didn’t think too much about it until he pulled up behind me at a set of lights.

The personalized plate confirmed that it was indeed my car, which made the subsequent events appalling. Evidently, my arm was draped across the back of the passenger seat. He then saw my hand stroking the young woman’s hair. Right before the light changed, he saw me lean over and kiss her.

Terrence’s blood boiled with rage. “What a jerk,” he thought. “How could Ron cheat on his beautiful wife?” He wondered what to do next. Should he confront me? Should he tell my wife? While he contemplated his response to my ethical lapse, the light turned green and the Maxima initiated its turn. That’s when Terrence got a better look at the driver and realized that my son had borrowed the Maxima–to pick up his girlfriend!

Terrence had partial information. When he saw my car, he assumed that I was driving it. And when he combined that partial information with the driver’s amorous actions, he filled those gaps with a worst case scenario. It’s just human nature.

Great storytellers setup their audiences. They reveal just enough information to let the audience’s imaginations run wild, then drop one last contextual piece that turns every worst case assumption upside down.

Don’t pile information upon your listeners. Present just enough detail to lead them down predictably wrong paths and drop the hammer.

Photo Credit: Harris & Ewing, photographer. Annapolis Maryland, 1934. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/hec2013007668/.

by Ron Ploof | Aug 7, 2017 | Business Storytelling

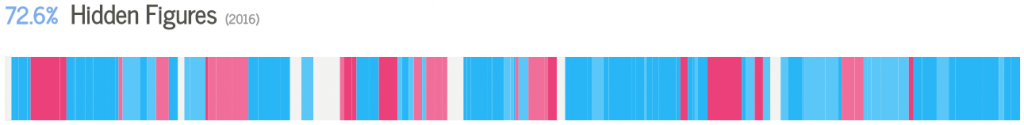

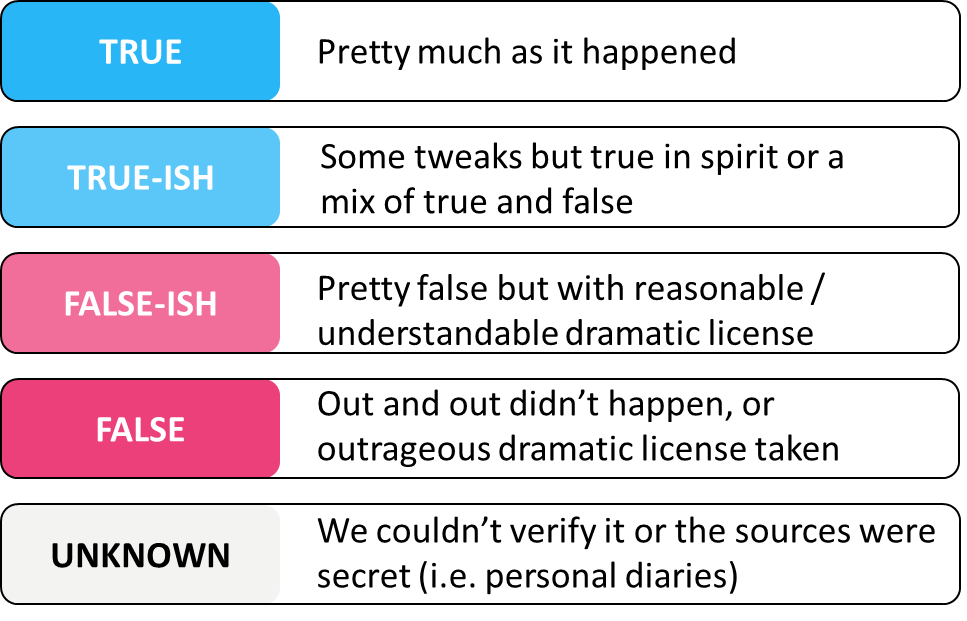

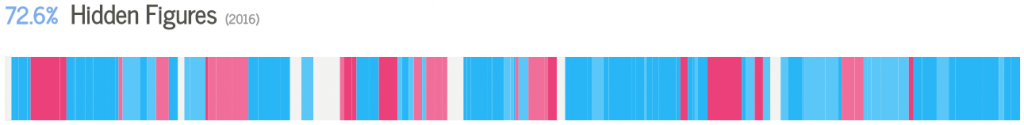

Information is Beautiful recently published an article, Based on a True Story, that fact-checked movie scenes and depicted the results graphically.

Here’s an example from the movie, Hidden Figures:

Each bar represents a scene and its “truthfulness.”

When I first saw this data, the 76.2% trueness rating felt slimy. I love this movie and want to believe that EVERYTHING in it was true. But, taking a step back, does it really matter?

Telling a story based on actual events is tricky because life is a jumbled mess of imperfect humans reacting to random situations. The human condition is hard enough to understand from an individual’s perspective let alone trying to explain it to someone else. And while audiences fully accept the premise that life is messy, they prefer their stories to be organized, and so they grant storytellers some leeway with facts.

We touched upon this concept almost two years ago with the post, Be a Storyteller, not a Liar.

“A storyteller makes up things to help other people; a liar makes up things to help himself.”

― Daniel Wallace

Storytellers have an ethical responsibility to help their audiences through entertainment, education, wisdom, etc.. Simultaneously, they must counterbalance that obligation by making stories interesting. And therein lies the ethical rub. Where do they draw the lines? How do storytellers choose which facts to use, omit, or modify while maintaining the story’s integrity?

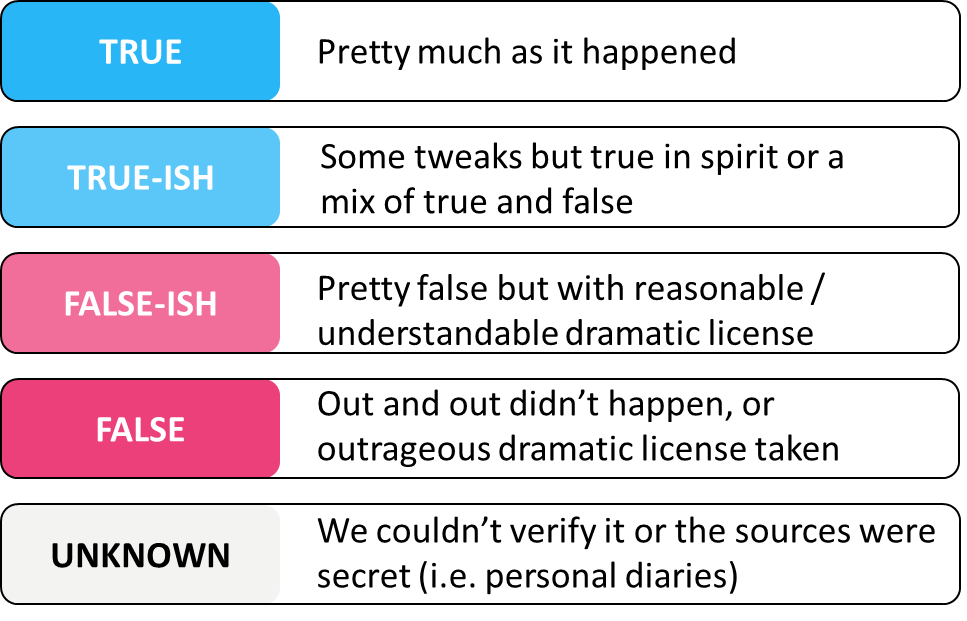

Let me introduce a tool called DOTS — an acronym that stands for Details, Order, Time, and Substitution.

Some details are more important than others. Therefore, storytellers must choose which details advance the story while eliminating all others. (See Take the Air Out of Bloated Content with Chekhov’s Gun). For example, one scene from Hidden Figures demonstrates the inhumanity of racism when Katherine is forced to use a separate coffee pot than her white co-workers. The coffee pot is important. It’s particular brand, model, and metallic finish, however, isn’t.

Stories don’t have to be told in the order by which they occurred. Life events, ABC, can be told as BAC, CAB, ACB, BCA, or CBA as long as the reshuffling helps the listener and doesn’t change the meaning. Hidden Figures uses flashbacks of Katherine learning math as a young girl to boost the meaning of present scenes.

Editing for time is the easiest of the storytelling edits to understand. While the Hidden Figures story spans several years, its storytellers obviously compressed time by using only 127 minutes to tell it.

Audiences accept, even encourage storytellers to play with time, whether it be through compression or expansion. Expansion is used when an event takes more time to describe than it took to play out. For example, have you ever had a moment where time stood still while you processed volumes of information in an instant? Malcolm Gladwell uses this technique often in his bestseller, Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking, where he dedicates several pages to describe a thought processes that only last for fractions of a second.

Sometimes precise facts hinder a story, requiring the storyteller to alter them. For example, what if Katherine arrived at a revolutionary concept after conversations with dozens of people? If the idea helps advance the story, does it really matter how she arrived at the idea? To save time, what if the storyteller combined all of Katherine’s conversations with a single one? As long as the substitution doesn’t change the meaning, the substitution passes the ethical tests.

DOTS is a tool that helps find the balance point without crossing ethical lines. The next time you need to tell a story based on true events, give it a spin.

Photo Credit: Fisher, Alan, photographer. [Grange & Zeller tackle / World Telegram & Sun photo by Alan Fisher]. Chicago Illinois, 1935. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2013646412/.

by Ron Ploof | Jul 31, 2017 | Business Storytelling

I had just come home from a drama-filled workday complete with frustration and a touch of irony–all the ingredients of a great story–and felt compelled to tell my wife immediately.

The story was awful. I was so caught up in the emotion of wanting to tell, that I neglected what it was like to listen. Rather than helping her connect with the story, I rattled off a cluttered jumble of both relevant and irrelevant facts.

It’s a common affliction. ANYONE that tries to tell a story without putting thought into it will create an unsatisfactory experience for both teller and listener.

A recent research paper, The Novelty Penalty: Why Do People Like Talking About New Experiences but Hearing About Old Ones? shed some light on the situation. Its researchers had set out to prove that people prefer hearing novel stories (those that they’ve never heard before) over stories that they’re familiar with. Their experiments, however, pulverized the premise.

The reason is that storytellers typically underestimate the difficulty of telling novel stories and the report lists three common pitfalls: “(a) they overestimate how well they understand what they hope to convey (b) they overestimate how much of their understanding is already shared by their listeners, and (c) listeners rarely tell them that these estimates are wrong.” 1

The first two findings ring true for me. I’m super confident in my abilities to tell a story yet I always tend to overestimate them when telling first-time stories in the moment. Yet, while it may be true that listeners won’t tell us that we did a crappy job, experienced storytellers don’t need to be told. We have a bead on our audiences. We can see when they’re leaning in or leaning back. We can see the confusion in their eyes. We KNOW when a story isn’t connecting because the most common issue comes from meaning gaps.

“Stories leave out far more information than they contain, and listeners can typically understand a story only if they have extensive background knowledge that allows them to fill the story’s informational gaps.” 2

Since Tara didn’t participate in my workday experience, she was forced to fill-in the missing concepts, feelings, and thoughts that were omitted through my exuberance to tell the story. Had I been diligent in connecting with her through a shared experience, she might have connected better with the story.

The report concurs. “…listeners may enjoy hearing familiar stories because they (a) contain significant amounts of novel information, (b) evoke rich personal memories, (c) allow speakers and listeners to bond over common experiences, and (d) allow listeners to gain information about themselves via social comparison.” 3

In other words, storytellers are obligated to maintain listener interest and help them see themselves in a story by delivering the right amount of new information interspersed with ample shared experiences.

The report perfectly summarizes the sacred responsibility of those who to choose to tell stories. A successful storyteller “…must strike a careful balance between…telling stories that are familiar enough to be understood, but novel enough to be worth understanding.” 4

Storyteller beware. Your role is to find that balance point. Any attempt to tell a story without finding it will result in an #epicfail.

Photo Credit: Con Colleano on a slack-wire, circa 1920, Public Domain.

Footnotes:

- Gus Cooney, Daniel T. Gilbert, and Timothy D. Wilson, “The Novelty Penalty,” Psychological Science 28, no. 3 (2017): , doi:10.1177/0956797616685870. p. 392.

- The Novelty Penalty p. 380.

- The Novelty Penalty p. 393.

- The Novelty Penalty p. 381.

by Ron Ploof | Jul 24, 2017 | Business Storytelling

The last time you purchased something online, you were probably asked to rate the product on a scale of one to five. Most product marketers love stockpiling 5-star reviews for two reasons: they demonstrate competitive superiority while simultaneously making their C-Suite execs feel all warm and fuzzy. However, while a mountain of 5-star reviews may look impressive, from a business storytelling perspective, they are less valuable than other ratings. Why? Well, let’s rank each from least valuable to most valuable:

| Rating |

Business Storytelling Value |

|

3-star reviews are worthless because they’re ambivalent. Ambivalence has no point and without a point, there’s no story to tell. |

|

5-star reviews are slightly more valuable, but they still don’t tell us very much. Sure the reviewer loved the product, but that’s it. There’s no context. Facts without context form the very definition of narrative as opposed to a story. |

|

1-star reviews form the basis of an emotional story. By choosing the lowest rating, the reviewer has found no redeeming value in your product or service. 1-star reviews are so negatively biased, however, that there’s nothing new to learn from the information. |

|

2-star reviews contain the ingredients of a complex story. While 2-star reviewers aren’t satisfied, they’ve at least found some redeeming quality in the product. 2-star reviews are target-rich environments for companies to uncover business stories because, unlike their 1-star counterparts, 2-star reviewers might be willing to tell both the good and bad sides of their experience. |

|

The most valuable business stories come from 4-star reviews. These reviewers obviously like the product or service, yet not enough to give it the top rating. 4-star reviews open up the possibility for product improvements. Many 4-star reviewers care about your product and therefore are open to providing exceptional feedback…err…if your company is willing to take it. |

Ratings and reviews offer ideas to make your products better. So, the next time you present your customer satisfaction data to upper management, skim over the 5-star reviews and focus on the 4 and 2-stars. These even-numbered ratings contain stories that will either make your products better or suggest ideas for creating entirely new ones.

Photo Credit: Bain News Service, Publisher. Whitehill. , ca. 1915. [Between and Ca. 1920] Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/ggb2006000977/

by Ron Ploof | Jul 17, 2017 | Business Storytelling

I forget where we were going, but I was riding in a kid-packed automobile driven by Mrs. Favreau, one of the neighborhood Moms. As we came around a corner, she said, “Okay, kids, we’re coming up to the singing bridge.” Her children let out a squeal. Evidently, this was a big deal in their household.

The rest of us kids looked puzzled. “Singing Bridge?”

“The bridge sings when you go over it,” the Favreau kids said excitedly. They seemed surprised we’d never heard it before.

I couldn’t get my head around the concept. How does a bridge sing? Like a song? I tried to imagine a bridge that sings Steely Dan, The Eagles, or Bob Seger.

As we approached, the Favreau kids got more excited. “Here it comes!”

I strained to look over the seat to see this special bridge. I recognized it, having crossed it many times before with my parents. I couldn’t remember any singing. But, if the intensity by which the Favreau kids bounced off the car interior was any indicator, we were about to have an over-the-top experience.

I felt the anticipation as the car approached the bridge. I was going to hear my first bridge song. That’s when the car’s rubber tires gripped and slipped their way across the bridge’s metal grating, which created a hum that sounded like bumble bees.

“Do you hear that? It’s singing!” the Favreaus cheered.

I heard it alright and felt disappointed. The bridge wasn’t singing–or at least not in the way that I’d expected. It might have been my first experience of feeling baited & switched.

The Hook (StoryHow™ PitchDeck Card #52) describes a storytelling technique that entices an audience to continue listening. Creating a great hook is complicated because storytellers must balance the level of the audience’s interest with the ability to deliver on the hook’s promise. The deeper the storyteller sets the hook, the higher the audience’s expectation, thus increasing the storyteller’s burden of delivering a satisfactory ending. The greater the mismatch between the expectation and the satisfaction, the greater the rejection of not only the story, but also the storyteller.

Beware of singing bridges. Set believable hooks that will eventually satisfy audiences–or be prepared to suffer the consequences.

Photo Credit: Historic American Engineering Record, Creator. Taiya River Bridge, Skagway, Skagway, AK. Alaska Angoon Dyea Vicinity Skagway Yakutat, 1968. Documentation Compiled After. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/ak0493/.

by Ron Ploof | Jul 10, 2017 | Business Storytelling

Most novices think that story development starts by focusing on the big things like the plot, the struggle, and the final resolution. But, that’s not where the magic of storytelling resides. The best storytelling lives in the little details that hit audiences in the gut, thus making us feel a kinship with the characters.

The Amazon Original Series, Good Girls Revolt is a period piece that’s loosely modeled on the story of Newsweek Magazine in the 1960s. One of the characters, a caption-writer named Cindy, is in a loveless marriage. One day, she has an encounter with co-worker, Ned, a photographer who has asked her to sit in a portrait chair so he can check his lighting.

At first, Cindy seems a little self-conscious as the sole focus of Ned’s attention. But when he reaches over after a series of test shots and adjusts the way her necklace dangles, her self-consciousness transforms into a moment where she looks at him dreamy-eyed.

Later that evening, Cindy and her self-absorbed husband are each reading in bed. He glances at her lustfully, closes his book, and attempts to initiate some…well…you know. But rather than reciprocating, Cindy rebuffs him. As he turns away, angry and frustrated, the camera draws our attention to her fingertips that are fondling her necklace. The scene fades out with her wearing the same dreamy smile that we saw earlier.

That’s great storytelling, folks. The writers have made brilliant choices about facts and the order they’re revealed. The scene with photographer Ned was used to set up a powerful moment where we KNOW what Cindy’s thinking…AND IT DIDN’T EVEN REQUIRE WORDS.

Symbolism (StoryHow PitchDeck Card #57) is an advanced technique that storytellers use to convey a deeper meaning. Symbols come in many forms such as graphics, props, or in this case, necklaces. Based on what an audience knows about a symbol’s significance, these devices can tell entire stories on their own. By establishing Cindy’s necklace as a symbol that represents a man’s caring touch, Good Girl Revolt’s writers have transformed a simple piece of costume jewelry into a powerful tool that connects the audience with the character.

So, stop worrying about the big pieces and start focusing on the little ones. Perhaps you can use a symbol in the next piece that you write?

Photo Credit: Cameron, Julia Margaret, photographer. Ellen Terry, at the age of sixteen / Julia Margaret Cameron., 1913. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/89708624/

| A StoryHow Puzzle: The 1913 photograph used in this post is of Miss Ellen Terry. I chose the photo because she’s holding onto a necklace, however I then stumbled upon a connection between it and the 1981 movie, Arthur, starring Dudley Moore and Liza Minelli. Can you find the connection? I’ll post the answer in next week’s Dragonslayer Digest. You are subscribed, aren’t you? |

![]()