by Ron Ploof | Jun 25, 2018 | Business Storytelling

“That’s a great question,” the interviewee said, inserting a long pause between the comment and her answer. I had flashbacks to similar moments where I was also forced to bide time to construct my response. And that got me to thinking. What was it about this particular question that made it “great?”

Great questions shed light on pivotal moments from our pasts. These unexpected epiphanies shift our minds into overdrive to extract meaning so deep that it’s impossible to answer with a single sentence. In other words, great questions require story-answers, thus we need additional time to work out the details, setup the premise, and deliver the conclusion.

- What made you start this business?

- What event made you who you are today?

- If you had to pick one moment to relive, what would it be?

- What single piece of advice would you offer your younger self?

Great questions are time machines that deliver us to the most influential moments from our pasts.

So, when was the last time someone asked you a great question and you had to think deeply about your answer? In all likelihood, you answered with a story.

Photo Credit: Wood, Thomas Waterman, Artist. Thinking It Over. , 1884. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2002723420/.

by Ron Ploof | Jun 18, 2018 | Business Storytelling

I’ve never had a problem staring at a blank page for hours on end. It’s always been easy for me to sit down and type. Don’t get me wrong. I probably don’t type about anything useful, but, the actual act of writing creates momentum that always takes me in a useful direction. Years of storytelling experience has taught me little tricks that help find that momentum–the most valuable being the test. I first wrote about testing in The Four-letter Word that Drives all Stories and will expand upon the concept today.

Tests work because they force something to happen. Positive test results indicate that things are on track while negative ones indicate that something must change. In other words, negative test results signal the beginning of a story while positive tests signal the end of one. And therein lies the rub for marketers who seek to be budding business storytellers. The problem is that most upper management forces their marketing teams to wear blinders that only allows them to see the positive test results. And that keeps the team from finding the real stories.

Think about the initial reaction a prospect had when first introduced to your product or service. Did the person like it? Was the reaction strong or tepid? Or perhaps the reaction was mixed—where the product fit from a functional perspective, but was too expensive, or the price was right, but adopting it would require massive changes in the way the customer did business. Such negative test results offer the beginnings of potentially great stories because something must change. Perhaps the customer will negotiate the price, find additional budget, or uncover an innovative way to transition from the old system to the new.

Negative tests are the basis for a cause-effect relationships and force counter-reactions. The stronger the negative test result, the stronger the counter-reaction, and the more interesting the story.

So, the next time you’re seeking marketing stories, try a test. Test your customer’s assumptions, theories, and their wills. If the results are positive, do one of two things: end the story or keep testing. Once you hit a negative test result, you’ll have found the beginning of your next story.

Photo Credit: Cassinelli, Pete, Bob Cassinelli, and William A Wilson. Bulldozer Freeing Tractor Stuck in Mud. , 1978. May. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/ncr000652/.

by Ron Ploof | May 14, 2018 | Business Storytelling

The statement, “journalists make the best storytellers” has always confused me. My issue comes from the their duty to report facts, which would limit them to narrative instead of storytelling. Journalists have an allegiance to the facts over their audiences.

Don’t take my word for it. Robert Siegel, famed co-host and journalist from NPR’s All Things Considered, described the difference between journalists and storytellers in an interview that he gave to Park Howell on Episode #140 of the Business of Story Podcast.

In the clip, Siegel recalls a conversation he once had with Ron Howard about his movie, A Beautiful Mind. Siegel asked Howard why a specific scene from Silvia Nasar’s book of the same name didn’t make it into the movie. Howard explained that “…it wasn’t part of the story line—the arc that we were choosing…” because he worried about losing the audience to it.

Here’s what the retired journalist had to say about Howards’s answer:

“For Ron Howard, a great filmic storyteller, to maintain the sympathy of the viewer…he crafted…a story…that omitted a…pretty salient fact about Nash’s life… There’s the difference between being a storyteller and a journalist; we (journalists)…can’t decide that if I leave out this salient fact from the story that people will listen longer. And in fact, we’re obliged…to find the point that might be hard to reconcile, that might disabuse a listener about some assumption about it, to probe to where…this story gets tough…It’s a big difference. And I think the challenge…for a journalist…is to be very mindful of the facts that we have to include in the story. Where we have to acknowledge where we got something from, even though that might harm the flow of the storytelling…but we’re bound to do that. We can’t just chuck it out because the story would be more streamlined and easier to follow.”

And hence my confusion. Journalist can’t be storytellers—by definition. Siegel is clear: journalists have an obligation to the facts; storytellers have an obligation to the audience and never the twain shall meet. If a journalist chooses to omit certain facts out of deference to the listener, then they’ve not only broken their sacred vow but may have ventured onto the slippery slope of activism. We might call such a leap as “fake news.”

Pandering to a particular audience by selectively editing the facts is more insidious than publishing bogus facts. We see this everyday with the cable news networks, for example, as both Fox News and CNN hand select facts that play well to their respective right and left-leaning audiences.

Journalists are beholden to facts. Storytellers are beholden to their audiences. While storytellers have more latitude than their journalism cousins, they too have their own code of ethics as we covered in Storytellers Tackle Ethics with DOTS. Storytellers are free to modify (D)etails, (O)rder, (T)ime and make (S)ubstitutions, as long as those substitutions serve the listener as opposed to the storyteller.

The one trait that journalists and storytellers share is the ability to write. The best journalists are masters of narrative. The best storytellers are masters of life and the human condition.

And never the twain shall meet.

Photo Credits: Delano, Jack, photographer. Don Jackson, a senior, delivering a news broadcast at the Iowa State College radio station. 1942. Library of Congress

by Ron Ploof | May 7, 2018 | Business Storytelling

The request comes in similar forms. “Ron, can you “bang out,” “throw down,” “slap together,” or “crank out,” a few PowerPoint slides for me?” Evidently, sharing one’s brilliant insight is as simple as communicating through bullet-speak.

Bullet-speak was developed at the turn of the twenty-first century. It’s a communicable disease that spreads from co-worker to co-worker as employees react to short-term requests that deserve longer-term reflections. The disease spreads effortlessly because bullet-speak requires very little skill. It only requires a host that can operate a mouse and pound hamhandedly on a keyboard to spray bullets with abandon. Rat-a-tat-tat.

Bullet-speak is easy. Storytelling is hard. Bullet-speak thrives on mindless reaction. Storytelling emerges from thought. Therefore, if employees are to have any shot at becoming better communicators, they’ll have to do more thinking. And therein lies the problem.

Henry Ford best described the monumental task before them. “Thinking is the hardest work there is, which is probably the reason why so few engage in it.” 1

Until organizations start rewarding the hard work necessary to convey meaning, they’ll continue to remain stuck in the language of bullet-speak.

But that would require change.

Rat-a-tat-tat.

And such a change would be terrifying.

Rat-a-tat-tat.

Business storytellers need their leaders to stand up for them–leaders like General James Mattis, the former commander of U.S. Central Command who once said that “PowerPoint makes us stupid.” 2 Organizations need leaders with guts, like Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, who not only banned PowerPoint, but he replaced it with something radical. He requires his employees to “…compose 6-page narrative memos, and he starts meetings with quiet reading periods—’study halls’—in which everyone reads the memo from beginning to end.” 3

As a storyteller, I’d welcome such an opportunity. But to be fair, I can also see how terrifying it would be for someone who had successfully navigated their career through a mastery of bullet-speak.

Can you imagine what is was like for those first Amazonians to present using subjects and predicates instead of bullet-speak? And while that change may have elevated their blood pressures, can you also imagine what it was like when they bared their souls before the ‘study halls’ as peers read those six pages in silence?

Since I’ve never been a part of one of these meetings, I can only imagine what would happen next. While It’s likely that the team will have a better dialog about the topic, I also see a potential side-benefit. Team building could emerge as future presenters reached out for help to craft better prose.

But alas, that would require the hardest work there is, which is why most companies will likely continue down the same bullet-ridden path.

Rat-a-tat-tat.

Photo Credit: Library of Congress, Henry Ford, photo taken by Hartsook circa 1919. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/94506959/

by Ron Ploof | Apr 16, 2018 | Business Storytelling

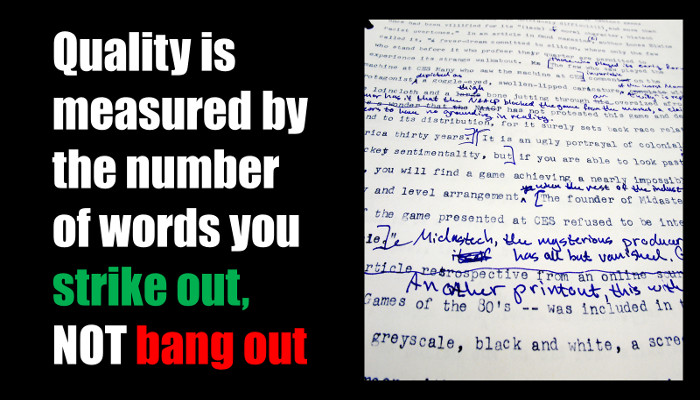

I learned a valuable writing lesson from a movie scene of Ernest Hemingway staring at the blank page. A piece of cardboard with handwritten numbers leans against the wall behind his typewriter. After an awkward moment, Hemingway pencils a zero onto the cardboard. As the camera pulls away, we see that it’s the third consecutive day with a zero. One of the world’s greatest writers reminds us that writing is a marathon instead of a sprint.

But, that’s not what I’ve been seeing recently, as more and more social media posts describe how someone “banged out” ten-thousand words of their next book over the the course of a weekend. Most of these posts are subsequently rewarded with dozens of congratulations for the accomplishment. This may sound curmudgeonly, but what exactly did they accomplish? It’s like congratulating someone for completing a marathon without doing any training. While it’s possible to complete all 26 miles untrained, it’s impossible to do it well.

Banging out ten-thousand words is an accomplishment, it just isn’t the accomplishment. Every good writer knows that those first 10,000 words will contain something like 2,500 nuggets of gold hidden among 7,500 pieces of iron pyrite. And the only way to separate them? Through the hardest part of writing: editing. Magic happens in the editing.

I’ve been working on a manuscript for over a year. Last weekend, I wrote 5,000 words, yet the word count on Sunday evening was actually smaller than the word count on Saturday morning. If I only measured my writing productivity through word count, last weekend would have been considered an #EpicFail.

But, that’s not my goal. My readers don’t care about how many words I’ve “banged out.” They only care about the ones that survived many rounds of ruthless editing.

It’s not the amount of words you write. It’s about the amount of words you keep.

Photo Credit: mpclemens published the image, A lot of ink spilled, through CC BY 2.0.