by Ron Ploof | Aug 13, 2018 | Business Storytelling

A couple of months ago, my grown daughter prefaced something with, “I forget the story, but this is what I took away from it.”

Her statement gave me pause because it changed my view on the relationship between message and story. Previously, I saw story as a permanent vehicle that delivered meaning from one person to another. Afterward, I saw story as more temporary–and I must admit–I didn’t like this revelation. I work hard to weave messages into my stories and have always considered them inseparable. But now, to think that messages could survive the stories that carried them? That was troublesome.

Then, upon further reflection, I realized that I was being selfish.

For the past three years, I’ve used this little corner of cyberspace to preach how storytellers must have empathy for their audiences. If I’m truly willing to follow my own advice, then I must admit that the audience cares more about the message than the story. As a result, rather than grieving the loss of a story, I should be celebrating the successful delivery of its message.

The role of any story is to pass meaning from one person to another. Good stories present the right words at the right time to both invoke and hold an audience’s interest long enough for them to make meaning. If that happens and wisdom is passed, does the delivery mechanism’s fate really matter? And to expand upon that concept, when enlightened audience members decide to pass their newfound wisdom onto others, do they need the original story to do so, or perhaps it’s best that they wrap the message into stories of their own?

It’s not about the story; it’s about the moral of the story.

The story is a shell whose sole purpose is to deliver the nut. It’s designed to last for as long as it takes to deliver its precious cargo, whether that’s to the ground where it grows roots or to a hungry mouth. Either way, the shell is cracked and discarded. That’s life. Some things give their lives for the sake of others and stories are no different.

The message is the nut. The story is the shell. And that’s alright by me.

Photo Credit: Horydczak, Theodor, Approximately, photographer. Animals. Squirrel side view, eating nut. Washington D.C, None. ca. 1920-ca. 1950. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/thc1995010295/PP/.

by Ron Ploof | Aug 6, 2018 | Business Storytelling

The question “What do you want on your headstone?” is an excercise with deep storytelling roots because it forces you to find your life’s throughline (StoryHow™ Pitchdeck Card # 40). I found my answer to the question many years ago.

He made the complex simple.

That’s what I do. I love to transform complex concepts into fundamental elements of human understanding.

Richard Feynman, the late Nobel Prize winning physicist, had an interesting way of testing his understanding of a complex concept by preparing a freshman lecture on it. If he couldn’t explain the concept to a classroom filled with high-school educated students, he concluded that he didn’t understand it himself, and therefore needed to go back to the drawing board.

I love that philosophy because professor Feynman puts the blame on himself, not the students. He, like all great storytellers, has empathy for his audience and thus takes responsibility for helping his students build upon their prior knowledge to arrive at the new knowledge.

His philosophy runs counter to a phrase that I despise. If you ever want to see me get a little heated, just say the following: “Ron, we need to dumb this down.” I hate this phrase because it belittles an audience. Audiences don’t need oversimplifications, they need someone who cares enough to teach them what they need to learn. Unfortunately, such teaching requires effort. But if done right, the effort is worth it.

Recently, I helped an engineer explain his new machine learning program. As with most brilliant people describing their work, he dove enthusiastically into too many details of how his invention worked instead of what it did. So, I asked him questions. Why was his program important? What problem did it solve? What are the implications of not having it? It took a while, but I began to understand who the program was for and why it was important to them. Finally, by embracing my own learning process, I found the path to help others understand it too. I didn’t dumb-down the concept–I bootstrapped my understanding to his, and then taught others how to do the same.

Dumbing-down is easy. Building up is hard. The human mind can comprehend complex concepts immediately if given the right context and frame of reference. It’s our job as storytellers to find that baseline concept and to build upon it.

Don’t dumb down. Build up.

Photo Credit: Thomas, Henry Atwell, Copyright Claimant. “The good-for-nothing” / W. Una chro. ; Raynor pin. , 1872. [New York City: Published by the American Chromo Co. No. 743 Broadway, New York City] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017660748/

by Ron Ploof | Jul 30, 2018 | Business Storytelling

“Why do you keep you doing that?” my sailing instructor asked.

“Doing what?”

“Why can’t you leave it idling?”

We’d been been practicing one of sailing’s most important skills: docking under power. While you might think that learning how to tack, run, or set a beam reach would be more important to learn, consider the odds of a collision when sailing in the open ocean as opposed to navigating through a marina packed with millions of dollars worth of boats.

The goal was to move as slowly as possible while still having full control of your boat. The instructor had taught me to set the engine lever to the idle position, but for some reason, I refused to leave it there. Instead, I’d give it a little extra gas, thus making the boat move a little faster and in turn, increasing the odds of colliding with some millionaire’s weekend getaway.

While my actions perplexed the instructor, I knew exactly why I was doing it. When I was a teenager, I owned a car that always stalled while idling. The only way to keep it running was to give it a little gas. Since the boat’s rough idling sounded exactly like my car just before it choke out, I reacted accordingly.

Little did I know that all boats sound like that in their idle position!

The StoryHow™ method is built upon the premise: a story is the result of people pursuing what they want, and so we frame our stories by defining its events, roles and influences. Let’s take a look at the base elements for this story.

- Event: Safely docking a sailboat under engine power

- Roles: Student and instructor

- Influences: Conflicting ideas of how a boat engine works

The influences make this story work. A simple misunderstanding in engine mechanics sets up conflict, confusion, and eventually forces the instructor to question his student.

We all bring patterns to our present situations and some of the best stories emerge from mismatches in those patterns. So, what patterns do your characters bring to a situation? How will you reveal them? Will you let the audience know and keep the other characters in the dark, or will you reveal the motivations to all and let the mayhem ensue?

We all bring patterns. Try playing with them to find your next story.

Photo Credit: https://www.loc.gov/resource/pga.11245/

by Ron Ploof | Jul 23, 2018 | Business Storytelling

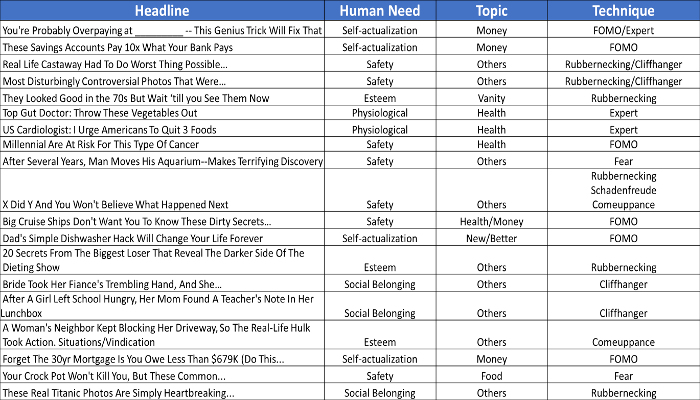

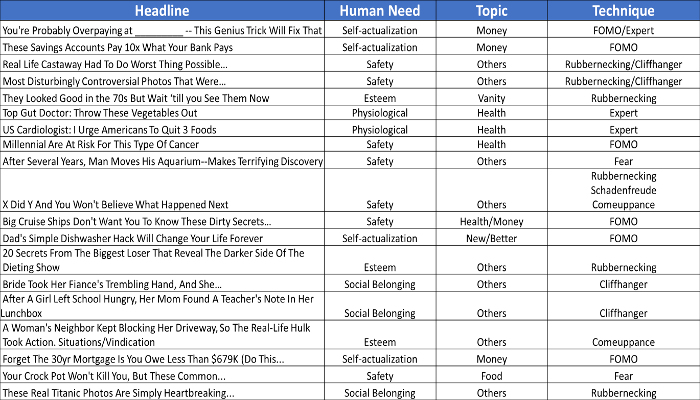

Last week, we discussed Shaggy Dog Stories–meandering missives that never find their points. This week, we look at the most nefarious form of Shaggy Dog Story: clickbait

The sole purpose of clickbait is to generate website traffic. Clickbait headlines are “effective” in that goal because they:

- appeal to our core human needs

- on topics that we find necessary

- while using storytelling techniques to make ’em all work together.

Human Needs

Maslow identified our human needs in his famous hierarchy:

- Physiological: We need life-sustaining things like food, water, and health

- Safety: We must have safety from life’s dangers

- Social Belonging: We need to feel as a part of a group and to be loved

- Esteem: We need recognition, status, and respect of others

- Self-actualization: We build upon the previous four to be the best that we can be.

Topics

Humans care about these topics:

- money

- food

- new/better

- health

- vanity

- the lives of others

Storytelling Techniques

Clickbait writers apply storytelling techniques to these needs and topics:

- Fear/FOMO: Things that we are afraid of…including missing out on a good thing

- Rubbernecking: Our insatiable need to look at the things that we should be looking away from

- Schadenfreude: Sometimes we get pleasure from the misfortune of others

- Comeuppance: We love it when Karma comes around

- The Cliffhanger: Someone is in danger and we want to know their fate

- Experts: People with the credentials to validate over-the-top statements

Here are some clickbait examples and how they use human needs, topics, and techniques. (Click the image to open a higher resolution version)

Don’t get me wrong, there is nothing wrong with using need, topic, and technique to write a great headline. The question comes down to intent. Are the headline writers serving themselves or the audience? Storytellers have empathy for their audiences while clickbait writers have disdain for them. Storytellers deliver on the promise of their headlines while clickbait writers grease the skids to their next Shaggy Dog story

Photo Credit: C.M. Bell, photographer. Garrett, Wm. dog. , 1894. [between February and February 1901] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2016697620/.

by Ron Ploof | Jul 16, 2018 | Business Storytelling

Have you ever heard a story that seemed so filled with promise yet it never delivered? While it had a great beginning, it then meandered aimlessly and never culminated into a satisfactory resolution? If so, you’ve been the victim of a Shaggy Dog story.

Here’s an example Shaggy Dog story.

Once upon a time there was a shaggy dog names Shaggy. One day, his owner entered the Shaggy into a shaggy dog contest. He won first place. After getting his trophy, Shaggy met up with his surfer friend, Floppy. The two drove to Zuma Beach where they rode the waves all afternoon. That’s when one of the waves carried Shaggy all the way to the beach where he met Shagita, the most beautiful shaggy dog that he’d ever seen. Shaggy asked Shagi out for burgers and milkshakes, but when the check came, Shaggy couldn’t find his wallet. Luckily, Floppy was in the next booth and lent him some money. And then…

See how the story shows promise yet never delivers? It dribbles information that seems relevant, yet the facts never coalesce into anything with significance. If you want to experience a modern day Shaggy Dog story, just go watch reruns of television show, Lost.

Two types of storytellers tell Shaggy Dog stories: bad/honest ones and good/deceitful ones. Bad/honest storytellers pile meaningless facts and arrive at pointless endings. But, there’s also something redeeming about them. We all have friends or family members who are terrible storytellers, but that’s what we love about them.

Good/deceitful storytellers, on the other hand, use their yarn-spinning skills to string audiences along. They know how to dole the right facts at the right time to hold an audience’s interest artificially. Since audiences can only take so much of this abuse, they eventually give up just as the good/deceitful storyteller laughs at how he yanked the audience’s chain.

Business storytellers must be on the lookout for long-winded expository lacking a point. A target rich environment for Shaggy Dog stories can be found in press releases that are filled with sycophantic praise, meaningless facts, and never deliver any form of resolution.

So, are you the creator or the victim of a Shaggy Dog Story? The only way to know is to pay attention.

Photo Credit: Mrs. Robt. W. Hopkins with English sheep dog, 4/19/26. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2016841986/